This week marked the centennial of the departure of the Australian Imperial Force (AIF) to partake in the Great War, and events have occurred around Australia to commemorate this. This week, I hand the keyboard off to The Warhawk for an overview of Australia’s entry into world military affairs as a significant independent player.

The Australian Government announced their intent to assist Great Britain against Germany on August 5, 1914, one day after the British declaration of war. However, the Australian Government found themselves ill equipped to assist the rest of the British Empire in the upcoming war. The Australian Army had been founded in 1901, and only existed for a scan 13 years. Furthermore it had been divided into two distinct groups; The Citizen Military Force and the Permanent Force. The former was a Citizen’s Militia and the latter was a small general staff of professional officers. A year prior to the opening of hostilities the Army had just over 2,000 professional soldiers. Complicating matters further was that the Defence Act of 1903 prevented the country’s soldiers from being deployed overseas.

The Australian Army needed an expeditionary force that was capable of deploying to Europe, and engaging the German Army. This would become the Australian Imperial Force (AIF). AIF was formed August 14, 1914 and its formation would be a major milestone in the History of the Australian Army. AIF would ultimately be the first Australian Military formation capable of performing a long duration military campaign overseas.

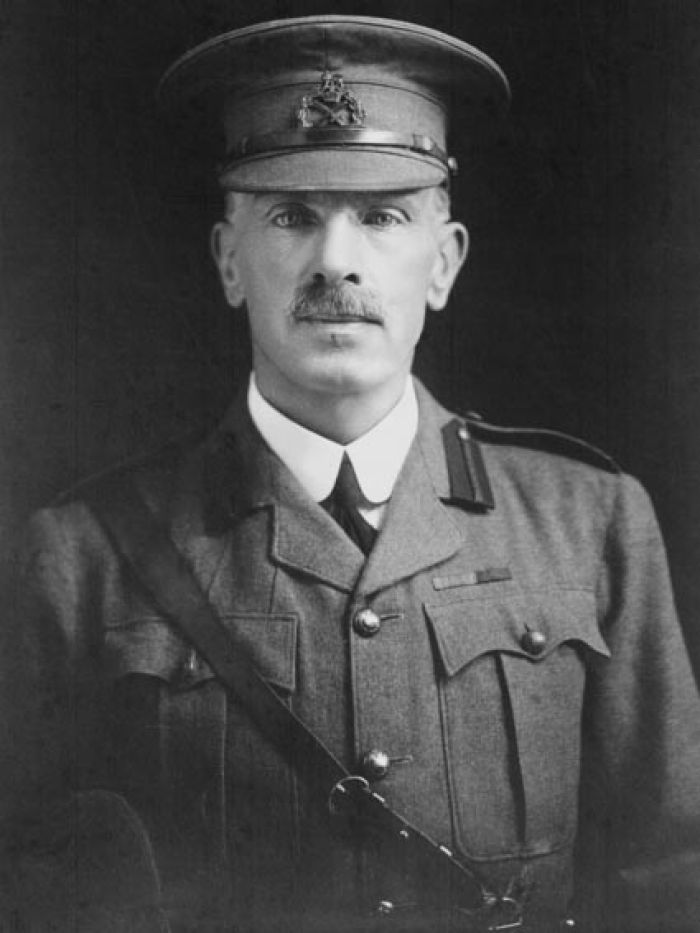

AIF was in many ways the brain child of General William Bridges. Bridges already had a prolific military career before the outbreak of the war. He had attended the Royal Military College of Canada (although failed to graduate) but joined the British Army and held a series of positions at the School of Gunnery. In 1899, he would serve in the Boer War and 10 years later be appointed Chief of Staff of the Australian Army. He also was the first commandant of the Royal Military College Duntroon.

General William Bridges, 1st Commander of the AIF |

Brigadier General Bridges’ first proposal for an Australian Expeditionary Force was to have a force of 18,000 men with 6,000 coming from New Zealand. However, this was changed at the behest of the Prime Minister Joseph Cook, to a single Infantry division, consisting of three brigades and a Light Horse Brigade to lend Cavalry support. This 1st Australian Infantry Division would be coupled with a second division comprising of two brigades, with one of the brigade originating from New Zealand. The second Division was named the New Zealand and Australian Division. These two divisions would provide the initial backbone of the new Australian Expeditionary Force. The name Australian Imperial Force was ultimately picked by William Bridges who was assigned the position of AIF Commanding Officer. With new Command, he received the promotion to Major General, making him the first Major General in the history of the Australian Army.

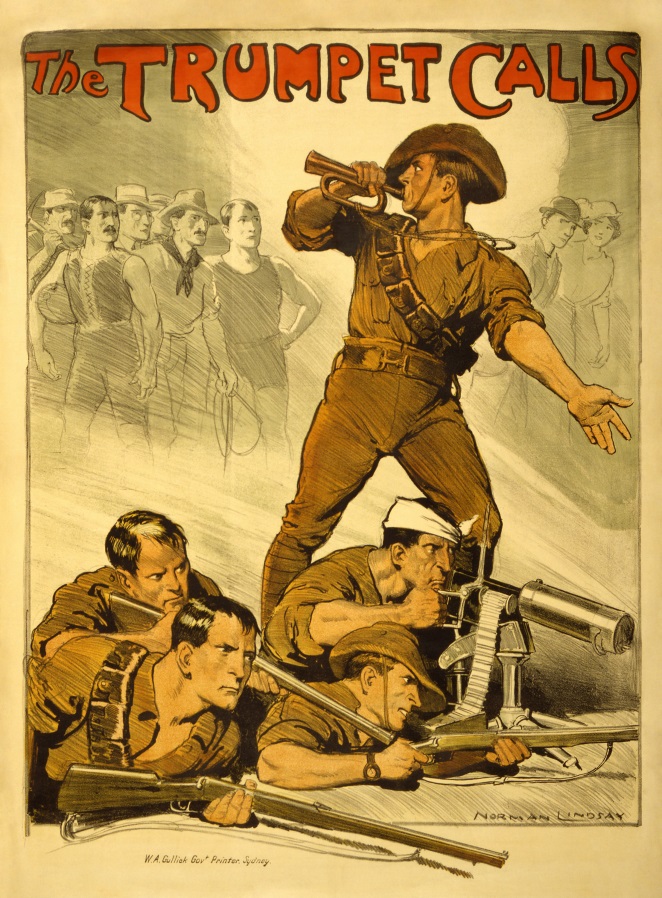

Despite the relatively meager population of Australia at the time (only around 4.9 million), the AIF was not short on Volunteers. By December of 1914, the AIF had received nearly 53,000 volunteers from across the Nation. In fact, every member of the Australian Armed Forces that saw service in the Great War was a volunteer. The first convoy of 38 transports carrying AIF Soldiers departed Albany, Western Australia on November 1, 1914.

Australian Naval and Military Expeditionary Force (AN & MEF)

The initial Australian military force to see combat in WWI was not the AIF but rather the Australian Naval and Military Expeditionary Force. This unit existed only very briefly in 1914, where it saw action against the Germans in their Pacific Colonies; New Guinea and the Bismarck Archipelago. At the time Great Britain feared that the German East Asia Squadron would conduct commerce raiding against British Shipping in the Pacific. Therefore, the British Government requested the Australian Army to destroy German Wireless stations and Coaling stations. It had to be done within six months.

AN & MEF Soldiers in Australia prior to their deployment |

The AN & MEF was founded with this task in mind, and the Australians had no problems finding volunteers. They scraped together a thousand soldiers and five hundred sailors (Find date of formation). The Infantry was known as 1st Battalion AN & MEF was drawn from volunteers in Sydney. Meanwhile the Naval Component was formed around almost the entire Australian Navy, including battlecruiser HMAS Australia, the cruisers HMAS Sydney, Melbourne, Encounter and the Destroyer Werrago. The Submarine AE1 also briefly took part in the campaign; however, she later went missing with all hands.

At dawn September 11, 1914 the AN & MEF arrived off the coast of Rabaul. It would be the first engagement involving the Australians. The Australians that landed found that the area was relatively lightly defended. After a small but fierce battle for the Wireless station at Bita Paka, and a brief siege of Toma, the German Government on Rabaul surrendered on September 17, 1914, with the final group of Germans and German aligned native soldiers surrendering on September 21. New Guinea and Rabaul would remain occupied by the Australians for the remainder of the war, and would later be given to Australia following the Armistice in 1918.

Sinking of SMS Emden

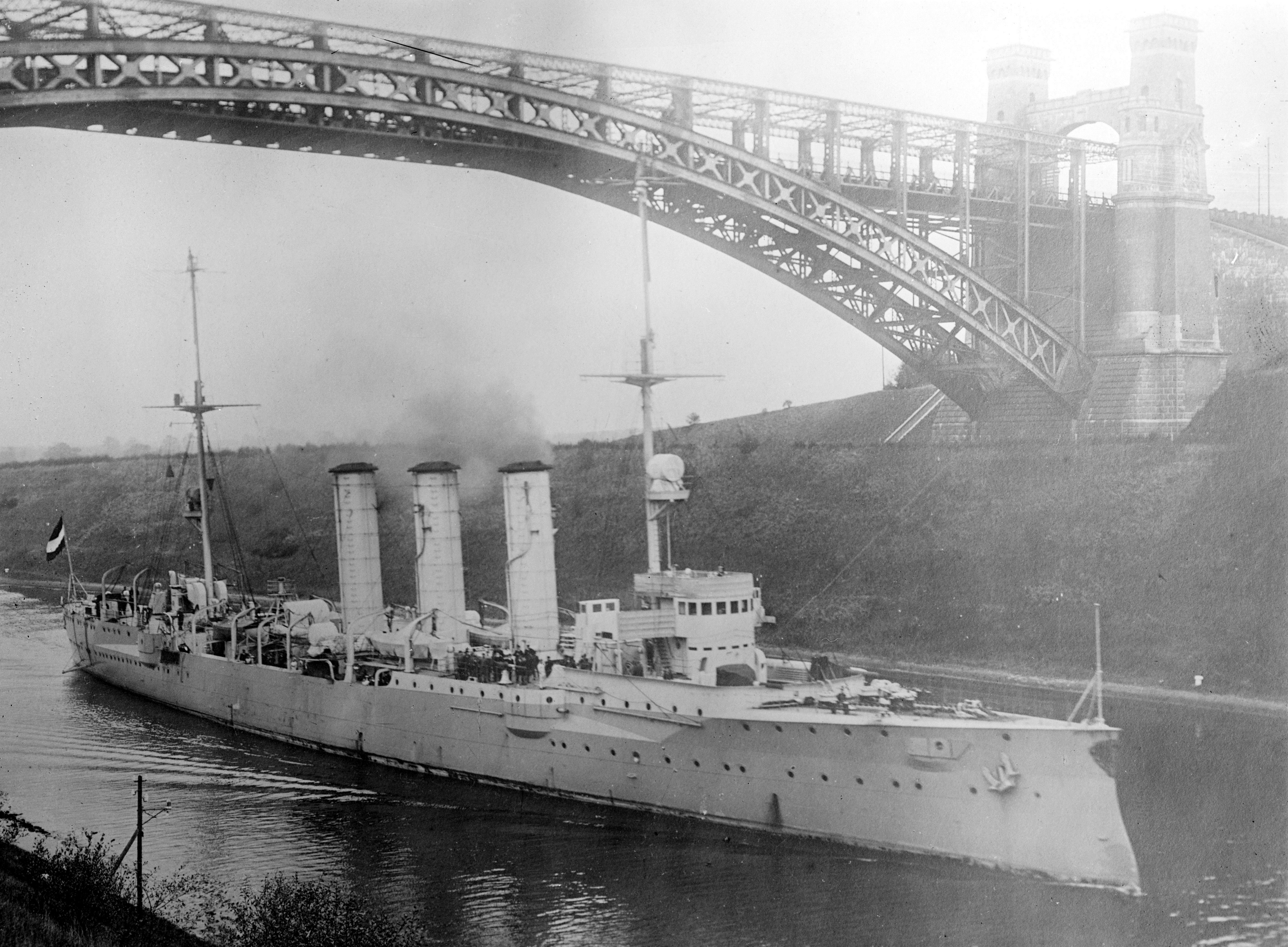

HMAS Sydney |

HMAS Sydney was one of the escort ships assigned to the first AIF Convoy, with her sister Melbourne, the British Cruiser Minotaur, and the Japanese Cruiser Ibuki. Sydney was a Town Class Light Cruiser constructed for the Australians only two years prior. Her commanding officer, Captain John Collings Taswell Glossop, would command her during the first Naval battle fought by the Royal Australian Navy. On November 9, the convoy received an inquiry from a British Wireless station in the Cocos Islands, some 50 miles away from the Convoy. The Station intercepted an unknown code, and radioed the Convoy escorts for assistance in identifying the code. Cocos followed their message with an identification report which described an unknown warship on approach, and finally an SOS.

The unknown warship was a Dreseden Class light cruiser SMS Emden. The Emden and her captain, Karl von Muller had been a thorn in the side of the Entente since the outbreak of hostilities. The vessel launched a highly effective raid on Penang which sank a French destroyer and a Russian Armored Cruiser. Emden had landed a party on Direction Island to demolish the British Wireless station.

A Dreseden Class Cruiser similar to SMS Emden |

Upon receiving the distress call, Sydney was dispatched to investigate the matter. At 0905 she sighted Emden and moved to engage. The German vessel fired the first two salvos of the battle. The initial salvo landed short of Sydney. The second didn’t. Sydney sustained heavy fire from Emden as she closed range to return fire. During this period Sydney sustained 15 hits which killed four sailors and wounded another sixteen. They would be the vessel’s only casualties during the battle.

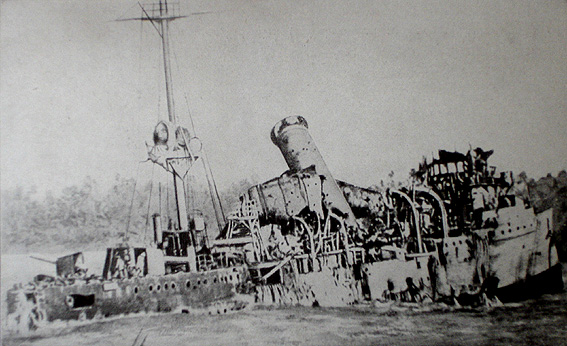

With the distance closed, Sydney returned fire. Despite being forced to engage at a closer range, Sydney had Emden outgunned. When the Australian vessel returned fire, the Emden was devastated. After repeated salvos from Sydney, the German cruiser had lost her masts as well as her fire control station. After sustaining hits to her steering gear and her engine room, Von Muller made the decision to beach SMS Emden along the coast of North Keeling Island. Seeing that Emden had been beached, HMAS Sydney broke the engagement to chase after the coaling ship Buresk, which had been resupplying Emden. By the time Sydney had intercepted Buresk she was already in the process of being scuttled by her crew. An Australian boarding party captured the Germans and Sydney delivered a final coup de grace before returning to Emden’s position.

Wreck of SMS Emden after her duel with the Sydney |

At the time of Sydney’s arrival at the Emden, the German cruiser was still flying her colors. HMAS Sydney signaled twice, via flag, asking Emden to surrender. When the German vessel didn’t return the signal, the Australians opened fire. With the ship wrecked, Captain von Muller ordered the Emden’s flag lowered, and a sailor to fly a white flag. Seeking to avoid their ship’s flag being taken as a prize, they destroyed the Imperial Ensign.

The Battle of Cocos was over. The Germans had lost two vessels and some 134 sailors. Another 39 were wounded, and all but a handful of German sailors were captured. The Emden landing party, send to destroy the Wireless station on Direction Island managed to commandeer a small vessel and sail to the Ottoman Empire. The battle was a significant achievement for the Royal Australian Navy. It was the first surface engagement fought by the Australian Navy in its history. As part of the greater strategic picture, the victory at Cocos, destroyed the sole German Commerce raider in the Pacific and Indian Ocean region. The remainder of the German East Asia Squadron would be destroyed off the coast of the Falklands later the following month during an attempt to reach Germany.

The Australians in Egypt and Beyond

The AIF Convoy diverted from its original destination, Great Britain, to Egypt. There was a lack of sufficient facilities for the Australians in Great Britain. The Australian and New Zealand soldiers would arrive on December 3, 1914 in Alexandria. Ultimately, the AIF would not see further action for the remainder of 1914. The AIF’s soldiers would spend the remainder of the year training in Egypt. In January and February of the following year the New Zealand and Australia Division would see service against the Ottomans during their raid on the Suez Canal, however, the bulk of the Australian Imperial Service would not see combat until April 25, 1915 at Gallipoli.

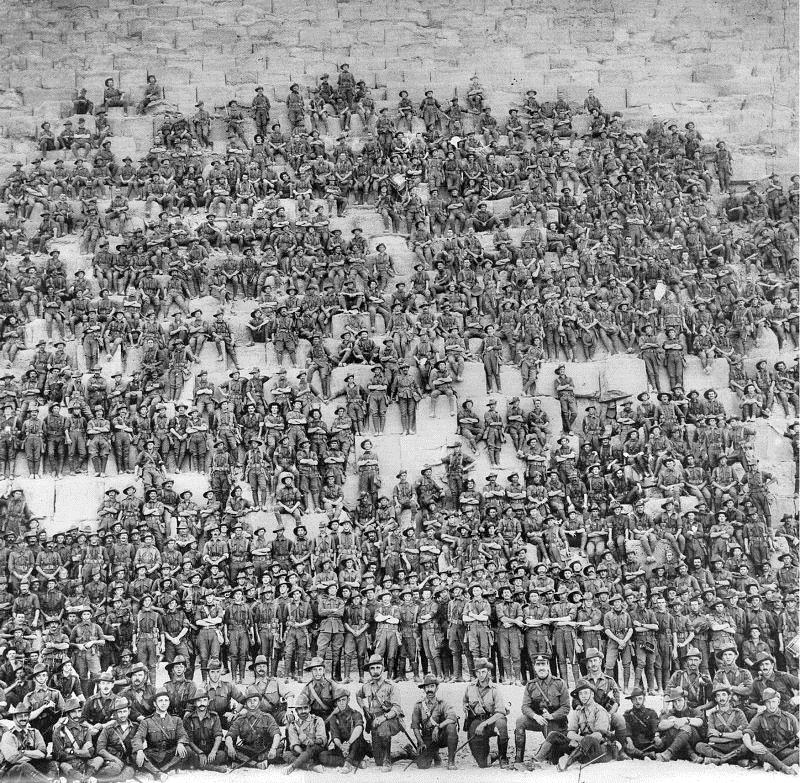

11th Australian Bn. on the Pyramid of Cheops at Giza, Egypt |

The Australian Imperial Force would see service in every theater of the war. Australians could be found in the jungles of New Guinea, the deserts of the Middle East and the trenches of the Western Front. Australian ‘Diggers’ served with distinction, 66 men would receive the Victoria Cross for valor in combat. By the end of hostilities in 1918, 331,781 Australians would serve overseas. Of this number, more than 210,000 personnel were listed as casualties, or 65% of the entire AIF, the highest of any belligerent nation in the Great War. Of that number 61,519 Australians made the ultimate sacrifice.

On a larger scale, the service of the Australian Imperial Force in the Great War was seen as a transformative moment in the histories of Australia and New Zealand. It has been seen today as a key moment in the formation of a national identity for both nations' citizens. Both nations were relatively young. The Commonwealth of Australia was only established in 1901, and the Dominion of New Zealand in 1907. The centennial of the AIF’s foundation marks the point where both nations stood up and played major roles for the first time on the international stage.

|

|

|