I am pleased to again hand off the keyboard to a guest writer and to see the return of author Ken Estes.

The origins of the amphibious assaults on Peleliu and Angaur in the Southern Palaus by the 1st Marine and 81st Infantry Divisions, respectively, under Operation Stalemate II [a most unfortunate name choice] in September 1944 remain complicated to this day. Suffice to say that the U.S. strategists who were always looking for ways to advance the timing of the Pacific offensive and seeking bypasses of Japanese islands and groups where feasible, simply missed this one. MacArthur's Philippines invasion in the end was not threatened by either the Palau or Caroline island group bases of the Japanese.

The Japanese had reinforced the Palaus hurriedly in 1944, using veteran units drawn from the Kwantung Army Group in Manchuria. Peleliu's garrison consisted of the 2d Regiment (reinforced) of the 14th Infantry Division, including a light tank company and several additional infantry battalions. These 6500 combat troops and 4000 service and labor troops would face the veteran 1st Marine Division, which had reequipped and retrained partially under severe limitations of their Pavuvu (Solomons) Island base.

In the aftermath of the Marianas Campaign the U.S. Marine Corps tank, amtrac and armored amphibian battalions received new vehicles to replace their battered machines. The 37mm tank cannon all but disappeared from the FMF, as the tank battalions discarded the last of the light tanks and new production LVT(A)-4 vehicles reached the armored amphibian battalions. Unfortunately these arrived too late to completely outfit the new 3d Armored Amphibian Battalion, which sailed for Peleliu with 24 of the older LVT(A)-1 vehicles. The amtrac battalions received new production LVT-2 and LVT-4 vehicles in a 1:2 ratio in 1944, and converted to all second-generation amtracs during 1945.

In contrast to the ultimate climactic battles of the war, however, the 1st Tank Battalion and 1st Amtrac Battalions would land with the 1st Marine Division at Peleliu, reinforced by the new 3d Armored Amphibian Battalion and the still-forming 6th and 8th Amtrac battalions. This fiercely contested battle, beginning on 15 September, presaged the violence of the 1945 island battles, and revealed the new Japanese doctrine of inland attrition defense, but also contained some parallels with the preceding actions. Once again, amtrac battalions were rushed into action with green commanders and crews. Shipping shortages caused the tank battalion to leave sixteen tanks behind. As experienced as the 1st Marine Division was, it had yet to make an opposed landing and in retrospect, its training and planning failed to meet the new standards already demonstrated in the Marianas operation.

D-day, the island is ringed with fire as amtracs and landing craft advance through the line of rocket and gun craft. (USN)

D-day, the island is ringed with fire as amtracs and landing craft advance through the line of rocket and gun craft. (USN)

Marines fight from the shelter of a disabled armored amphibian (USMC)

Marines fight from the shelter of a disabled armored amphibian (USMC)

After hiding from the typical three-day naval bombardment, the Japanese defenders came alive upon the approach of amtracs, armored amphibians and tanks of the 1st Division. The Japanese now knew that they had to stop the medium tanks and these drew much fire. Most all tanks received hits, but only three fell disabled out of the drive to the beach, guided by assigned amtracs from each of their LSM craft. But 26 amtracs already burned on the reef, and the 30 tanks that landed so quickly (30 minutes) after the assaulting infantry could not act everywhere at the same time.

Some others took cover behind a DUKW while landing vehicles burned. (USMC)

Some others took cover behind a DUKW while landing vehicles burned. (USMC)

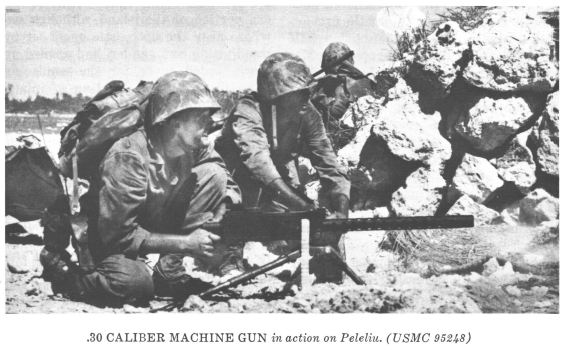

Too many Japanese emplacements had survived and now hammered the troops dispersed across the beaches. The armored amphibians, many armed with only the 37mm gun, dueled bravely with the Japanese as the tanks rolled ashore to reinforce.

M4A2 Tanks of A Company, 1st Tank Battalion on the airfield. Note all .50 caliber HMGs replaced by .30 Cal guns.

M4A2 Tanks of A Company, 1st Tank Battalion on the airfield. Note all .50 caliber HMGs replaced by .30 Cal guns.

This was ordered to increase .30 ammo capacity and firepower. (USMC)

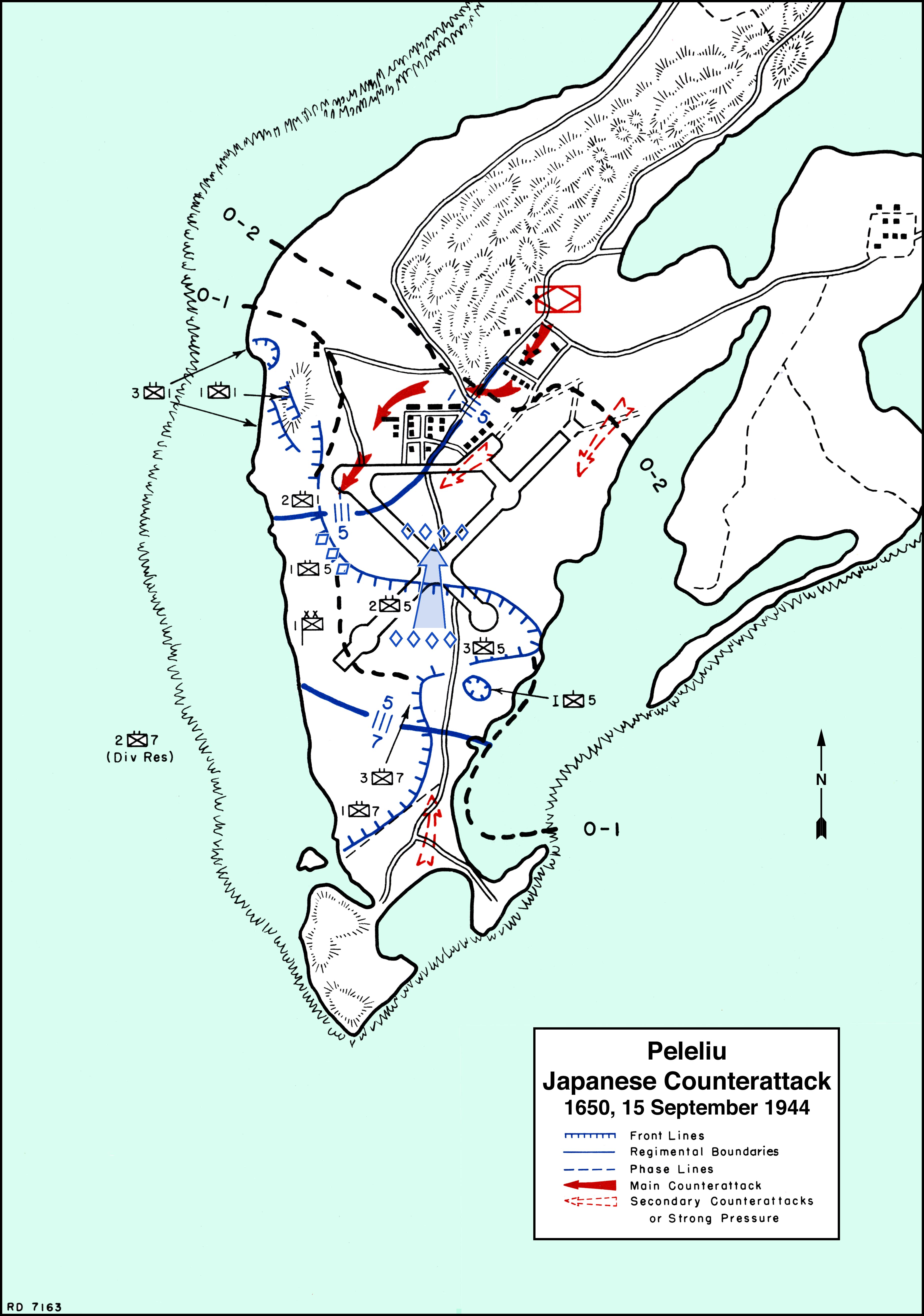

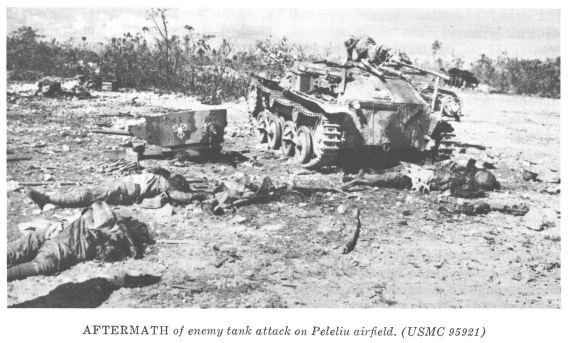

Slowly the tank-infantry teams edged forward, reducing the defenses, pillbox by pillbox. At about 1630, too late to save his beach defenses, the Japanese commander launched his 15 Type 95 Ha-Go light tanks against the 1st and 5th Marines on the edge of the island's airfield. The Japanese tanks gave it their best effort, racing ahead of their infantry to close the distance quickly, with many infantrymen riding the wildly plunging vehicles. Some of these were apparently lashed to the tank sides and rear using 55-gallon oil drums. The 1st Tank Battalion's crews responded in kind, some hurrying back from rearming at the beach. They proved more than enough to stop the Japanese attack. Platoons of tanks engaged the enemy formation, and infantry turned bazookas, 37mm antitank guns, and .50-caliber machine guns, all lethal against the Type 95, against the oncoming tide. Even a Navy divebomber chanced overhead, adding a 500-pound lb. bomb to the fracas. The tankers switched from armor-piercing to high-explosive ammunition as they saw their solid shot passing all the way through the light tanks. Amazingly, the speed alone of the onslaught carried several surviving tanks into the artillery in the rear, before they could be shot up and destroyed.

The apparent victory did not impress the strong-willed commander of the tank battalion, though. Lt. Col. Arthur J. Stuart did not hesitate to call attention to the defects evident in this battle in perhaps controversial tones. In his later assessment of the Battle for Peleliu for the official histories, he criticized landing-force planning for tank employment, and remarked that the destruction of the Japanese Army’s tank-infantry counterattack left "no grounds for smugness in regard to our antitank prowess. Had the Japanese possessed modern tanks instead of tankettes and had they attacked in greater numbers the situation would have been critical."

The islet of Ngesebus was seized on the north shore by tank, amtrac and infantry assault.

The islet of Ngesebus was seized on the north shore by tank, amtrac and infantry assault.

In his own study of tank doctrine for base defense, written in 1946, Stuart noted the Peleliu example thus: "A Japanese tank company attacked our beachhead at H+6 hours. It was entirely unsupported. This attack succeeded in penetrating our beachhead but did little damage as the Japanese tanks became easy prey to our tanks as a result of the Japanese tank commander's decision to fight a tank versus tank action with a platoon of our more powerful Shermans. This decision can only be logically explained by the Japanese commander's apparent ignorance of the great superiority of our tanks. Nonetheless, this operation is believed significant because (1) the Japanese tanks suffered no damage during the prelanding bombardment by naval gunfire and air; full strength survived to attack after H-hour and (2) the deployed Japanese tank counterattack successfully penetrated our naval gunfire isolation fires (neither NGF nor air inflicted any loss even though naval gunfire and air liaison teams were by that time ashore with forward infantry). Important is the fact that the Japanese tanks were undamaged and that the full complement of the island's tanks penetrated our defense."

A unique description of the battle came from LtCol. Robert W. Boyd, commanding 1st Battalion, 5th Marines, as he saw the Japanese Type 95s "...running around wildly, apparently without coordination, within our lines firing their 37mm guns with the riders on these tanks yelling and firing rifles." As seen by LtCol. Lewis Walt, a veteran of Tarawa and later assistant commandant of the Marine Corps, there was a reason for such chaos, as "...four Sherman tanks came onto the field in the 2/5 zone of action on the south end of the airfield and opened fire immediately on the enemy tanks. These four tanks played an important role in stopping the enemy tanks and also stopping the supporting infantry, the majority of which started beating a hasty retreat when these Shermans came charging down from the south. They fought a running battle and ended up in the midst of the enemy tanks."

Apart from the destruction of the Type 95s that day, the rest of the Peleliu battle consisted of tireless efforts by the tankers to support the infantry daily, despite breakdowns and battle damage. The second day's effort by 1st Tank Battalion came only after ammo was stripped from disabled tanks, such had been the consumption on D-day. Tank and infantry coordination quickly set in as tank radios, weapons and shelter against enemy fire directly aided all but a few infantry advances. They also escorted the USN armored flamethrower tried out for the first time, with two tanks attached the vulnerable amtrac. The battalion averaged only 20 operable tanks per day, even when the 16 others arrived from Pavuvu. Of the tanks landing on D-day, only one remained undamaged, the othes having at least one day out of action. Nine were total losses. Among the tank battalion's 31 officers, nine died in action and 13 others suffered wounds.

The thoroughly exhausted 1st Marine Division pulled out of Peleliu when relieved in mid-October by the 81st Infantry Division, which had suffered more casualties than the single Japanese battalion defending Anguar Island, but remained fresher and had a regiment still in corps reserve when the new mission came. It completed the assault and mopped up the island with the help of the army 710th Tank Battalion and USN flamethrower LVTs. Peleliu was declared secure on 24 November, but posed a crushing example of the kind of fighting that lay ahead as forces closed on the Japanese home islands. Casualties were high, and almost approached the Japanese total casualties of 10,695 killed and 202 captured:

1st Marine Division:

1,252 killed, 5,274 wounded or missing

81st Infantry Division:

542 killed, 2,736 wounded

Total: 1,794 killed, 8,010 wounded or missing

Army tanks and infantry finish the seizure of Peleliu. (USN)

Army tanks and infantry finish the seizure of Peleliu. (USN)

Further Reading:

Croizat, Victor J. Across the Reef. London: Blandford Press, 1989.

Estes, Kenneth W. Marines Under Armor: The Marine Corps and the Armored Fighting Vehicle, 1916-2000. Annapolis: USNI Press, 2000.

_____________. Tanks on the Beach: a Marine Corps Tanker in the Great Pacific War, 1941-1945, with Robert M. Neiman. College Station: Texas A&M University Press, 2003.

_____________. US Marine Corps Tank Crewman 1941-45: Pacific. Oxford: Osprey Publishers, 2005.

Gilbert, Oscar E. Marine Tank Battles of the Pacific. Conshohocken, PA: Combined Publishing, 2001.

Zaloga, Steven J. U.S. Marine Corps Tanks of World War II. Oxford: Osprey Publishers, 2012.

_____________. Armour of the Pacific War. London: Osprey, 1983.

-----------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

[1] Victor J. Croizat, Across the Reef (London,1989), 134-36; George W. Garand and Truman R. Strobridge, Western Pacific Operations, Vol. IV, History of U.S. Marine Corps Operations in World War II (Washington, 1971), 91-105.

[1] Steven Zaloga, Armour of the Pacific War. (London, 1983), 27.

[1] Garand and Strobridge, 122-26.

[1] Ibid., Zaloga, 30. The Navy Bureau of Ordnance had developed a Mark I flame thrower with a 100 yard range for possible use in landing craft, sending several of them to Hawaii in 1944 for testing. Six arrived in the 1st Marine Division base at Guadalcanal in time for the Peleliu operation and the Marines mounted them in LVT-4s. With a 200 gallon tank, they could fire for 74 seconds and proved useful, despite the vulnerabilities of the vehicle. Kenneth W. Estes, Marines under Armor (Annapolis, 2000), 93.