It's not intentional, but this does seem to be Ken Estes month on the Hatch. The keyboard again gets handed over for his description of the tank fight at the Mantanikau River.

Japanese Tanks against the Guadalcanal Perimeter: Action on the Matanikau River (23 October 1942)

The 1st Marine Division had sailed from North Carolina to New Zealand, less the 7th Marines, already tapped for the Samoa Defense Forces. The division began to unload at Wellington from transports in July, 1942 and made an administrative camp at Petone Beach, NZ. Maj. Gen. A. Archer Vandergrift, the 1st Marine Division commander, anticipated a training period of several months to bring the division into fighting trim, after which it and the 2d Marine Division of the new I Marine Amphibious Corps would likely see action in the various Allied offensives projected for 1943. Now, however, a limited offensive was already in the planning stage as the division crossed the Pacific in various convoys. The alarming spread of Japanese detachments south and east of Rabaul threatened the vital sea lanes supporting Australia and the bases from which the Southwest Pacific Command wished to launch its campaign to recover the Philippines. Pacific Fleet forces would land units of the 1st Marine Division in the Guadalcanal-Tulagi area to take the nearest Japanese advance air and seaplane bases and block any further advance. The islands thus seized would later serve as jumping-off bases for the planned reduction of Japanese positions at Rabaul and the northern coast of New Guinea.

Allied Lines of Communication, Southwest Pacific 1942

Allied Lines of Communication, Southwest Pacific 1942

Shipping and reinforcements in theater proved scarce for Operation Watchtower, the official name of the amphibious landing, and the 2d Marines with attached supporting companies was added via direct sailing from Camp Elliott (San Diego) in the United States. The shipping shortages and hurried reloading at Wellington contributed to a disheartening rehearsal landing exercise in the Fiji Islands, whence the task forces headed for the objective area. Only Companies A and B of 1st Tank Battalion and Company C of 2d Tank Battalion (with the 2d Marines) would go with the assault troops, and the Headquarters of the 1st Tank Battalion remained at Petone Beach, with its D Company.

An M2A4 light tank of A Company, 1st Tank Battalion offloaded into LCM-3 landing craft, Guadalcanal (USN)

An M2A4 light tank of A Company, 1st Tank Battalion offloaded into LCM-3 landing craft, Guadalcanal (USN)

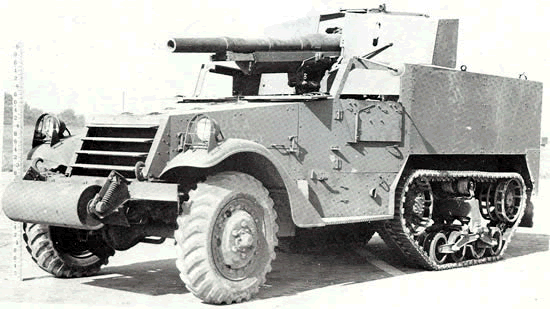

Vandegrift left most of his motor transport behind as well, but took all of the 130 LVT-1 tractors of 1st Amphibious Tractor Battalion, reinforced with A Company, 2d Amtrac Battalion. Also embarked for the landing was the divisional 1st Special Weapons Battalion, which included its three antitank batteries, each equipped with a 75mm platoon (2 gun motor carriages, M3) and a towed 37mm platoon (6 guns). The AT batteries were intended to be used at the division level to reinforce antitank divisions of the infantry regiments, each of which had its own identical antitank company of one 75mm and three 37mm platoons.

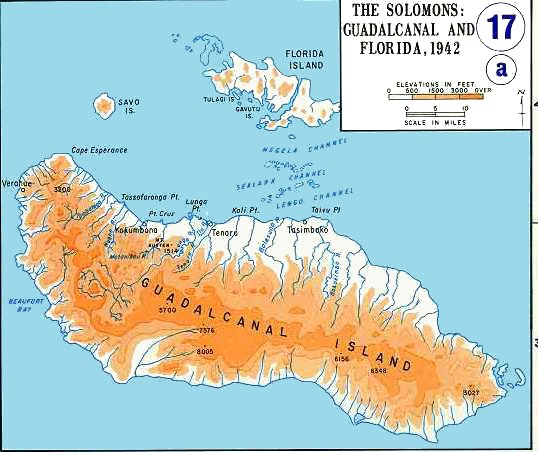

Guadalcanal and adjacent islands

Guadalcanal and adjacent islands

M3 GMC (US Army)

M3 GMC (US Army)

As was the case with the divisional tank battalion, the fielding of the M3 75mm gun motor carriage (GMC) by the Marine Corps in the original marine division came as no accident. With Germany on the offensive, pre-war planners anticipated that USMC forces might be employed not against Japan as previous war planning had held, but instead against the Wehrmacht. With only 37mm guns available in current US Army tanks and infantry weapons, the Corps had to rely on the new army tank destroyer program to obtain heavier caliber guns.

M3 GMC in action on Tinian with 2d Marine Division, 1944. Most of its missions were direct fire support of infantry, for Japanese armor was seldom engaged in the Pacific War. (USMC)

M3 GMC in action on Tinian with 2d Marine Division, 1944. Most of its missions were direct fire support of infantry, for Japanese armor was seldom engaged in the Pacific War. (USMC)

The weapon system built around the new halftrack personnel carrier was the M3 GMC armed with surplus M1897 guns, the famous “French 75” of WWI fame. The Corps initially ordered only 30 M3s of the 60 desired in January of 1942, because only 30 of the M1897 guns were on hand. The new Army M5 3" motor carriage then became the approved replacement as the Marine Corps standard “heavy self-propelled antitank weapon.” However, the Army canceled the M5 program and none of its other tank destroyers seemed to be light enough for amphibious landings. The shortage for three marine divisions and two antitank battalions totaled 87 tank destroyers. Belatedly, headquarters ordered 219 more M3 carriages with guns and ammunition from the Army in the fall of 1942. In the end these proved more than sufficient because only the 2nd Antitank Battalion was fielded for the amphibious corps troops, and it only formed in San Diego 1 September 1942 and disbanded at Noumea, New Caledonia on 17 December 1943, soon after its arrival. [i]

Thus, with a total of 12 75mm GMC and some 36 37mm towed antitank guns, the typical marine division had plenty of antitank firepower for the Japanese tank forces it faced.

Hell’s Island

The testing of the 1st Marine Division on Guadalcanal came all too soon, however, and the loss of naval superiority soon after its landings on Guadalcanal and Tulagi Islands on 7 August 1942 placed the division in a siege condition until that December. Early actions against the Japanese showed that the light tanks were frail and difficult to employ in rough terrain, were vulnerable to close assault by Japanese infantry and could be penetrated at will by Japanese 37mm AT guns. Accordingly, General Vandegrift placed his two tank companies in division reserve, near the vital Henderson Airfield and his command post, from where they would provide a decisive counter to any penetration of the U.S. force beachhead.

M2A4 and M3 tanks on Guadalcanal were operated by A and B Companies, 1st Tank Battalion respectively; this was the only combat employment of the obsolescent M2A4 light tank. (USMC)

M2A4 and M3 tanks on Guadalcanal were operated by A and B Companies, 1st Tank Battalion respectively; this was the only combat employment of the obsolescent M2A4 light tank. (USMC)

After preliminary skirmishes to enlarge the USMC perimeter, the 1st Marine Division went over to the defensive, awaiting reinforcements, particularly its own 7th Marine Regiment, now detached from Samoa garrison duty. It planned to base the perimeter on two-battalion strongpoints each on the Matanikau River to the west and the Tenaru River to the east, where the only trails led into the perimeter. However, too few units stood ashore to maintain a strong presence on the Matanikau.

A Marine patrol crosses the Matanikau River. (USMC)

A Marine patrol crosses the Matanikau River. (USMC)

The Battle of Henderson Field

The Japanese Seventeenth Army continued to push its forces to Guadalcanal, aiming at a major offensive on 9 October. Lieutenant General Haruyoshi Hyakutake landed on the island to take personal charge. In his haste, he left most of his 38th Division in the upper Solomons, except for two battalions. The honor of crushing the Americans would instead fall to the 2nd Division of Major General Masao Maruyama. In addition to survivors of the previous skirmishes and the September attack against Bloody [Edson’s] Ridge, Hyakutake’s forces also included an infantry regiment and three battalions of heavy field artillery, two battalions and one battery of field antiaircraft artillery, one battalion and one battery of mountain artillery, one mortar battalion, one tank company, and three rapid-fire gun (AT) battalions. Some engineer, service, and a few special naval landing force troops were also on the island. Some 20,000 Japanese soldiers thus represented their maximum buildup on Guadalcanal by mid-October.[ii]

Major General Masao Maruyama (US Army)

Major General Masao Maruyama (US Army)

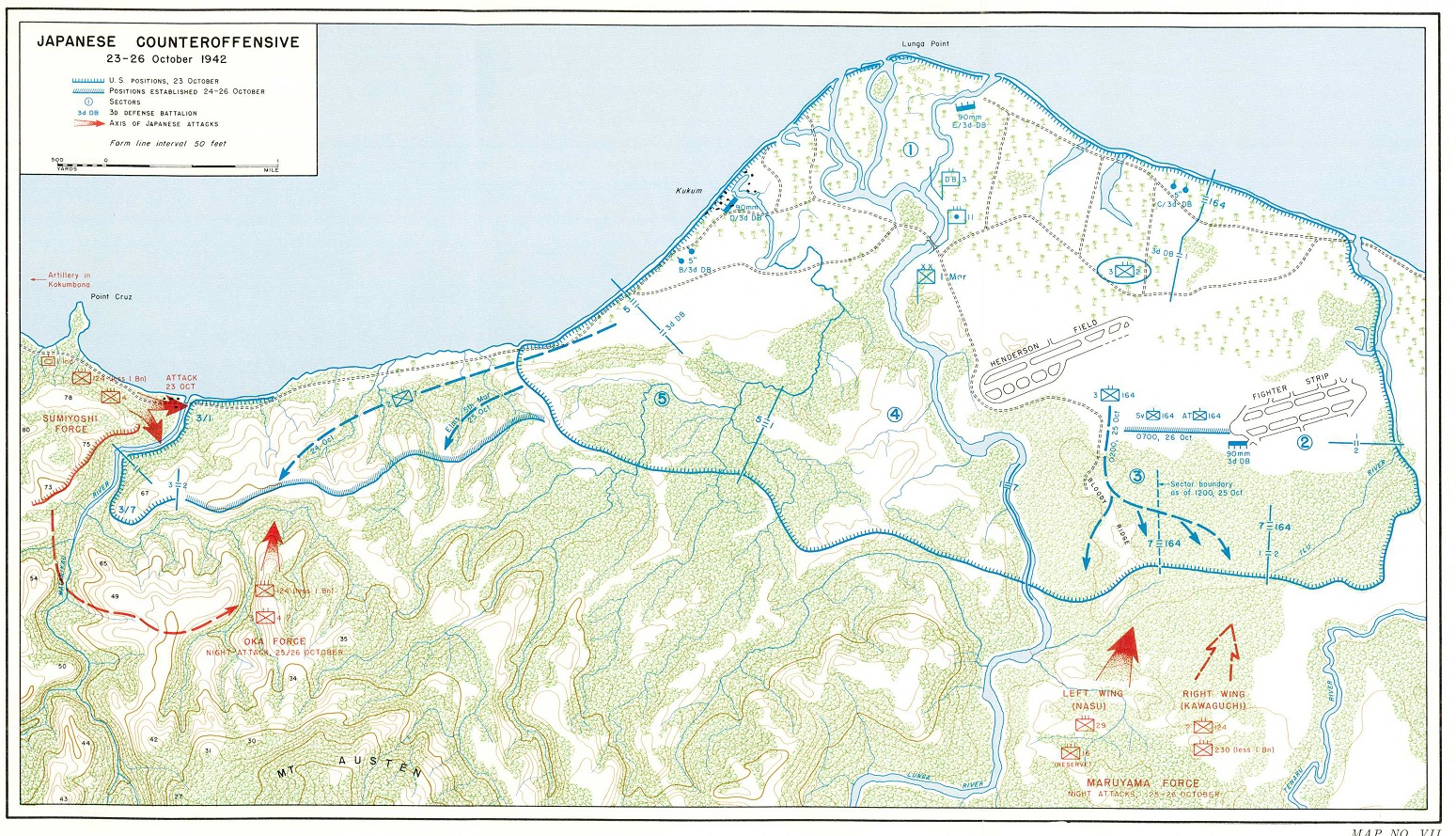

Fortunately for the 1st Marine Division, higher headquarters had decided to make a stronger effort to preserve the Guadalcanal position. In addition to the 7th Marines, the army’s 164th Infantry began to land on the island in October. Vandergrift could now occupy his Matanikau strongpoint just days before the Japanese attacked. He sent two marine battalions and part of the 1st Special Weapons Battalion to occupy a horseshoe-shaped position, running from the river mouth along the east bank to a point about 2,000 yards inland. Their right flank curved to cover the ocean frontage and the left flank turned east along the ridge line of Hill 67.

Battle of Henderson Field 23-26 October 1942; Japanese Movements

Battle of Henderson Field 23-26 October 1942; Japanese Movements

While the bulk of General Maruyama’s 2nd Division (reinforced) traipsed through newly cut inland paths, a key detachment of Hyakutake’s command moved toward the Matanikau in order to open the engagement penetrate the Henderson Field defenses and hold the Americans at bay while the 2nd Division enveloped the U.S. position from inland. The units in Major General Tadashi Sumiyoshi's coastal attack force included the reinforced 4th Infantry Regiment as well as elements of three Heavy Field Artillery Regiments and several mountain artillery and antiaircraft artillery units, and tanks of the 1st Separate Tank Company.

Coordination broke down for the Japanese, as the inland forces could not keep on schedule and the coastal force made contact sooner than expected against the USMC strongpoint on the Matanikau.

First contact took place on 20 October as a Japanese infantry advance unit approached with two tanks. A 37mm gun in the lines of 3rd Battalion, 1st Marines, hit one of the tanks and the unit retreated. As the sun set the next day, the Japanese tank company and supporting infantry tried to force the sand bar on the ocean frontage. In this case 37mm fire drove them back with the loss of one tank.

Marine Corps artillery of 11 Marines supported the front lines from positions on Koli Point. These are 75mm pack howitzers of the direct support battalions.(USMC)

Marine Corps artillery of 11 Marines supported the front lines from positions on Koli Point. These are 75mm pack howitzers of the direct support battalions.(USMC)

Artillery fire fell on the Marines the next day, 22 October, but 2d Division was not yet in position for the general attack. Maruyama postponed the assault to 23 October, but on that day he again postponed to 24 October.

Japanese Tanks Attack

But Semiyoshi launched his attack on the 23rd, with a heavy artillery barrage at 1800. Again came nine Japanese tanks, a mix of Type 97 mediums and Type 95 light tanks, and they drove onto the sand bar while the 124th and 4th Infantry massed in the jungle against the river line. Marine artillery crashed down on the Japanese infantry while the 37mm guns flayed the Japanese tanks. Eight of the tanks were stopped, with several on fire, while the last one broke through the wire of the marine infantry positions. When a rifleman threw a grenade into its tracks the tank turned and ran for the water’s edge, coming to a halt, apparently stalled out. This was the moment for the nearby 75mm GMC which came forward to pointblank range and destroyed it.

Wreckage of the Japanese 1st Independent Tank Company on the sandbar at the mouth of the Matanikau River on Guadalcanal after the failed October, 1942 offensive to take Henderson Field. The tank to the left is a Type 95 light, as is the one second from right; the other three are Type 97 mediums. (USMC)

Wreckage of the Japanese 1st Independent Tank Company on the sandbar at the mouth of the Matanikau River on Guadalcanal after the failed October, 1942 offensive to take Henderson Field. The tank to the left is a Type 95 light, as is the one second from right; the other three are Type 97 mediums. (USMC)

No Japanese infantry made it across the Matanikau that evening and no Japanese tank left the sand bar in either direction. The 1st Marines took 25 KIA and 14 WIA, but estimated 600 Japanese killed. Three more tanks were found disabled west of the river, probably knocked out by Marine artillery fire.[iii]

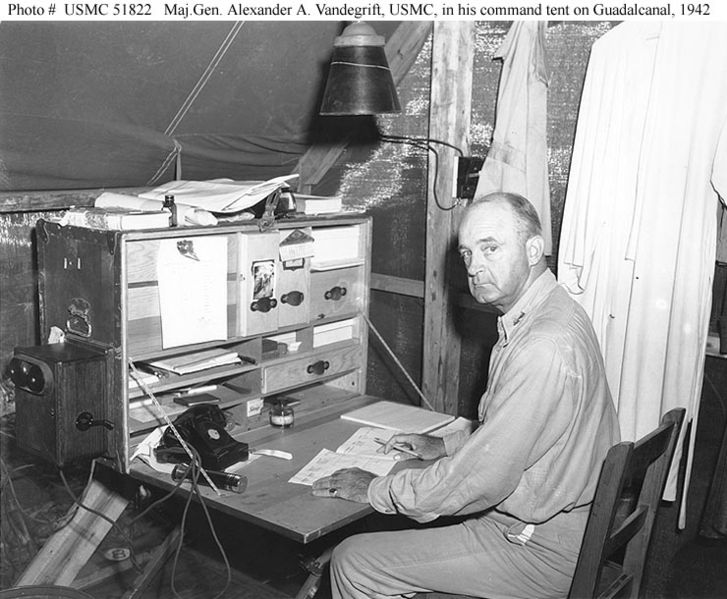

MajGen Vandergrift in his command tent on Guadalcanal. (USMC)

MajGen Vandergrift in his command tent on Guadalcanal. (USMC)

Aftermath

The defeat of the Japanese heavy forces at the Matanikau presaged the rout of their main infantry force that had not yet reached the line of departure. Their turn came on the nights of 24 and 25 October. As difficult as the subsequent Battle of Henderson Field was, it was nothing like the Japanese plan to cross the Matanikau and set up heavy artillery to pound the American perimeter while Japanese ships and aircraft piled on the heat once Henderson Field was bombarded and crippled.

Ironically, this action proved in a microcosm the basic US tank destroyer doctrine, for the 37mm guns and 75mm GMC destroyed the Japanese tank attack and the two USMC tank companies remained unused throughout the decisive battle.

Kenneth W. Estes

Further Reading:

Estes, Kenneth W. Marines Under Armor: The Marine Corps and the Armored Fighting Vehicle, 1916-2000. Annapolis: USNI Press, 2000.

_____________. Tanks on the Beach: a Marine Corps Tanker in the Great Pacific War, 1941-1945, with Robert M. Neiman. College Station: Texas A&M University Press, 2003.

_____________. US Marine Corps Tank Crewman 1941-45: Pacific. Oxford: Osprey Publishers, 2005.

Frank, Richard B. Guadalcanal, the Definitive Account of the Landmark Battle. New York: Penguin Group, 1990.

Gilbert, Oscar E. Marine Tank Battles of the Pacific. Conshohocken, PA: Combined Publishing, 2001.

Zaloga, Steven J. U.S. Marine Corps Tanks of World War II. Oxford: Osprey Publishers, 2012.

[i] Memo Dir P&P to CMC: 26Aug42: antitank artillery; CMC to QMMC 7Sep42; RG127/E18/1227; P&P internal memo 7Jan42 announcing Army 3” gun motor carriage (tank destroyer). Penciled memos: Director P&P to M-3 [operations staff officer]: “for consideration: a tank destroyer Bn in Div Spl Trps and a tank destroyer btry in each Def Bn….” M3 to Director: “We already have on order 60 mounts for 75mm guns for the same purpose. Suggest we follow development with view to possible substitution for 75mm or added weapon later. Believe we should put M-H tanks in Defense Battalions when we get more scout cars and M-3 tanks for divisions. “[overwritten in red pencil “M-3 OK [initials]”}; QMMC to Ch BuOrd: 20Jan42 requests 30 75mm motor gun carriages with mounts without gun, 75mm, M1897, USMC to provide guns, RG127/E18/1228. On the M5 motor carriage, see Hunnicutt, Stuart, 295-96.

[ii] John Miller, Jr., Guadalcanal, the First Offensive, United States Army in World War II (Washington, 1949), 137-156.

[iii] Frank O. Hough, Verle E. Ludwig and Henry I Shaw, Pearl Harbor to Guadalcanal, Vol. I, History of U.S. Marine Corps Operations in World War II (Washington, 1958), 332-337.