For this Hatch, I hand the keyboard over to guest author Ken Estes, LTC USMC (Ret). This week 68 years ago was the assault on Eniwetok

Eniwetok 17-22 February 1944: USMC vs. JA tank company

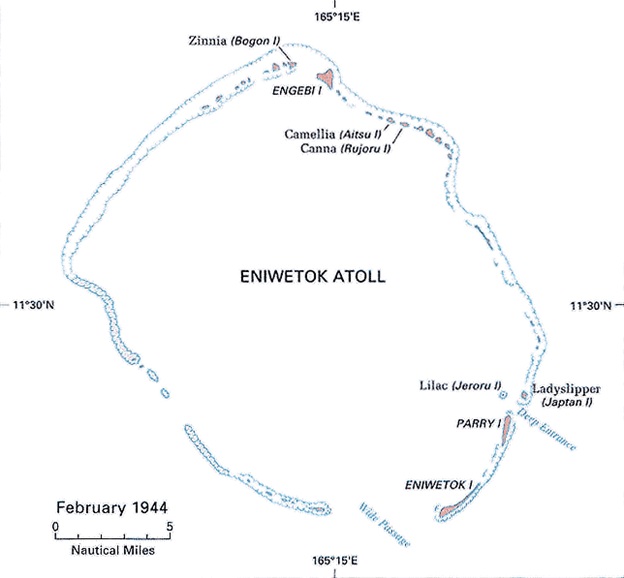

The U.S. Central Pacific commanders had slated the joint assault on Eniwetok Atoll for April 1944, in wake of the seizure of Kwajalein atoll and various lesser islands to secure the Marshall Islands. However, the Kwajalein operation had succeeded well in face of no interference from the Imperial Japanese Navy, and planners saw an opportunity to advance the schedule. Accordingly, Brigadier General Thomas E. Watson's Tactical Group 1, V Amphibious Corps, was alerted to assault the three major islands of Eniwetok, Engebi and Parry in quick sequence.

Click here for an animated timeline

Watson disposed of two regiments, the 22d Marines and the 106th Regimental Combat Team, plus artillery and scouts. Although the 106th included a regimental light tank company, the 2d Separate Tank Company (USMC) would support each landing with its M4A2 medium tanks.

The two separate tank companies formed by the Marine Corps in 1942 literally had been orphaned by their parent 1st and 2d Tank Battalions, the commanders of which had refused to deploy to the South Pacific with any of the Marmon-Herrington light tanks that the Corps had acquired first in the mid-1930s. The two company commanders left behind with a collection of Marmon-Herringtons [http://marmon-herrington.webs.com/usmc.html] found themselves attached to two new regiments deploying to Samoa to release two regiments of the 1st and 2d Marine Divisions, concurrently releasing their two tank companies to their parent battalions.

Thus, the 2d Separate Tank Company had settled into island defense duties at Samoa, under the 3d Marine Brigade. But all was not lost. The USMC quartermasters made good on their promises to furnish M3 light tanks as part of the normal refurbishment cycle. The tankers trained hard with the infantry battalions of the 22d Marines, and tank-infantry tactical coordination for island defense and counterattacking of landings stood them in reasonably fine condition for island assault. In addition, when the weaknesses of light tanks were revealed at Tarawa, the separate tank battalions received their M4A2 mediums as well as the divisional tank battalions.

Under the guns of battleships and cruisers accompanying the assault shipping of Rear Admiral Harry W. Hill, the landing force expected to make short work of an atoll on which little enemy activity had been noted so far. However, as usually the case, the enemy failed to cooperate with the attackers. On 4 January, the Japanese army's 1st Amphibious Brigade unloaded a detachment consisting of 2,586 troops on the three islands and belatedly began to prepare defenses in earnest. The detachment included the brigade's tank company of nine Type 95 light tanks.

The U.S. Navy's bombardment commenced 17 February and the 22d Marines assaulted Engebi Island, believed to be the strongest defended of the atoll. Following the wave of armored amphibians and three waves of infantry (two battalions) boated in LVTs, the tanks of 2d Separate Tank Company (Capt. Henry Calcutt) landed in their LCMs from USS Ashland (LSD-1). Resistance was light and the island was easily overrun, including three Japanese light tanks used as pillboxes. One USMC tank was lost when the landing craft had a bow ramp failure and the tank sank in 50 feet of water, 500 yards from shore, with only one crewman surviving.

The attackers then launched the 106th RCT the next day against Eniwetok Island, initially with two battalions, supported by the Marine separate tank company. Planners considered that island weakly defended, and the 22d Marines were to assault Parry only two hours later. Eniwetok Island actually had a tough defense to crack, though, with both underground and surface fighting positions, including concrete pillboxes, immobilized tanks, and wire barricades. Once ashore, the soldiers and Marine tankers had to deal with a counterattack force of 3-400 men drawn from the rest of the island's defensive positions. Admiral Hill postponed the Parry Island assault and landed a battalion of 22d Marines to reinforce. Belatedly, the U.S. infantry began to overcome the Japanese defenders, and the M4A2 tanks expended several full loads of ammunition before the resistance was quelled, on 21 February.

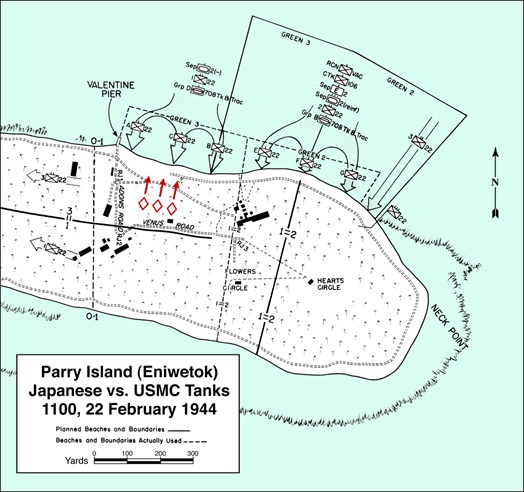

Feverishly servicing their tanks on board Ashville, the tankers of the separate tank company landed the next day in the third wave. This time, the three light tanks of the Japanese garrison were not deployed as pillboxes, but had ramps built into their revetments so that they could counterattack. Parry Island was also the headquarters of the Japanese brigade commander and contained his tactical reserve. The fight was on.

No sooner had the Marine tanks unloaded than the Type 95s counterattacked the advancing rifle companies of 1st Battalion, 22d Marines. Capt. Calcutt's tankers destroyed them with 75mm fire in short order. "If they had attacked the infantry before tank support arrived,” commented one of the 1/22d officers, “the battle for Parry Island would have been very bloody, indeed.” Instead, Parry Island fell that day. Tanks and infantry mopped up on 23 February. The 3d Battalion, 106th Infantry landed that morning as the assigned garrison force.

The lessons of Tarawa showed well in the Marshalls Campaign, and the heavier weapons of the landing force with better naval air and surface fire support proved their worth at Eniwetok, even when the Japanese garrison proved larger and more combative than intelligence had presumed. As would continue to be the case, a Japanese general would later observe, "the enemy's strength lies in his tanks."[1]

2d Separate Tank Company met all its tasks and more. It fought continuously for five days, including three different beach assaults, fighting by day and repairing afloat by night. "No other unit...performed as efficiently for s long as did this tank company."[2]

Kenneth W. Estes

Further Reading:

Estes, Kenneth W. Marines Under Armor: The Marine Corps and the Armored Fighting Vehicle, 1916-2000. Annapolis: USNI Press, 2000.

_____________. Tanks on the Beach: a Marine Corps Tanker in the Great Pacific War, 1941-1945, with Robert M. Neiman. College Station: Texas A&M University Press, 2003.

_____________. US Marine Corps Tank Crewman 1941-45: Pacific. London: Osprey Publishers, 2005.

Gilbert, Oscar E. Marine Tank Battles of the Pacific. Conshohocken, PA: Combined Publishing, 2001.

[1] Lieutenant General Mitsuru Ushijima, before the invasion of Okinawa.

[2] Jeter Isely and Philip Crowl, U.S. Marines and Amphibious War, (Princeton, 1951), 327.