For the last part of his three-part series, I yet again hand over the keyboard to Mr Harry Yeide. - The_Chieftain

Normandy: Second-Largest American Armored Amphibious Assault.

The Saipan operation is far eclipsed in the popular memory by the landings that had taken place in Normandy, France, only nine days earlier, but for the men of the armored force, the Pacific assault was a bigger show. Sixty-eight Army amtanks participated in the assault wave at Saipan, as compared with 102 amphibious and fifty-nine wader-equipped tanks at Omaha and Utah Beaches, but to that must be added 200 Army-crewed amtracs at Saipan.

Operation Overlord was to be the symphony of the style of amphibious operation developed from the painful learning experiences in North Africa, Sicily, and Italy. Dependence on the infantry to clear landing areas for tanks in Operations Torch, Husky, and Avalanche had weakened the assault waves’ ability to handle counterattacks, and commanders determined that the doughs would enjoy close tank support on the Normandy beaches. The Allied armies would shell the beach, storm the beach with infantry and tanks, and secure the beach.

The first separate tank battalions destined to participate in the invasion of France—including the 70th, 743d, and 745th—arrived in the United Kingdom between August and November 1943. Preparation before D-Day included refresher training, exercises with partner infantry divisions, familiarization with landing craft, waterproofing of equipment, and orientation with special equipment built for the invasion. Three battalions selected to go ashore with the first invasion wave in Operation Overlord received special and secret training for a scheme that embodied the purpose of the separate battalions: Giving the infantry close-in gun support throughout combat operations. Two companies each of the 70th, 741st, and 743d Tank battalions were to land minutes before the first infantry, riding special amphibious duplex drive (DD, also known as “Donald Duck”) M4A1 Sherman tanks to shore. The third medium tank company and battalion tankdozers would follow in landing craft.

A Duplex Drive M4 with its rigging down.

A Duplex Drive M4 with its rigging down.

A DD with screens raised.

A DD with screens raised.

A DD tank under power reveals its limited freeboard.

A DD tank under power reveals its limited freeboard.

Developed by the British, the DD conversion to the M4 Sherman series added a collapsible screen and thirty-six inflatable rubber tubes or pillars attached to a boat-shaped platform welded to the hull of the waterproofed tank. When inflated, the tubes raised the screen, which was locked into position by struts. The assembly acted as a flotation device, allowing the tank to displace its own weight in water and giving the vehicle about three feet of freeboard. The tank was driven through the water at seven to eight miles per hour by two eighteen-inch movable screw propellers, which also acted as rudders, attached to the back of the hull and powered through a bevel box off the track idler wheel. Between 15 March and 30 April 1944, the 743d Tank Battalion conducted 1,200 test launches from landing craft at Slapton Sands, losing only three M4A1 tanks and three lives.[i] The DD-equipped battalions exercised on a restricted beach to maintain secrecy until D-Day, which meant that the men had no opportunity to practice with their infantry partners.[ii]

Major General Charles “Cowboy Pete” Corlett, who in April had taken command of XIX Corps and had led the 7th Infantry Division in its assault on Kwajalein, was appalled that planners were ignoring the lessons of the Pacific war. Why was the first wave of infantry not riding to the beach in armored LVTs, he wanted to know? His observations were brushed off, as if anything learned in the Pacific was “bush league.”[iii]

After delays caused by awful weather, the date was set: D-Day was to be 6 June 1944, and H-hour was 0630. A massive flotilla off the coast of Normandy readied itself to launch the largest amphibious operation in history, all air, land, and sea components taken into account.

The invasion plan called for elements of one corps to land at each of the two American beaches: V Corps at Omaha and VII Corps at Utah. Later, XIX Corps would become active in the area between the two lead corps, and the 116th Infantry of XIX Corps’ 29th Infantry Division had accordingly been attached to V Corps for the assault.[iv]

Weather conditions at H hour were actually somewhat better than predicted, with fifteen-knot winds and eight-mile visibility. Heavy bombers struck coastal defenses on the British beaches and Utah Beach, but low clouds forced bombing on instruments at Omaha, which resulted in most ordnance being dropped to the rear. At 0550, the naval flotilla opened its bombardment of the Omaha and Utah beach defenses. The battlewagons and cruisers fired until just before the troops hit the sand, at which time rocket gunships and other close-support vessels took up the task.[v] A vast armada of landing craft headed for the coast of France. The German Seventh Army’s war diary noted, “Strong seaborne landings of infantry and tank forces beginning at [0615] hours.”[vi]

70th Tank Battalion Shermans load onto a Landing Craft, Tank (LCT) in Kingswear, England, on 1 June 1944. These Company C tanks beat the amphibious duplex drive tanks to Utah Beach in Normandy on 6 June, a screw-up that worked out well.

70th Tank Battalion Shermans load onto a Landing Craft, Tank (LCT) in Kingswear, England, on 1 June 1944. These Company C tanks beat the amphibious duplex drive tanks to Utah Beach in Normandy on 6 June, a screw-up that worked out well.

The Good News: Utah Beach

Except for a standard military issue of screw-ups, such as putting troops ashore far away from their assigned landing spots, the Utah Beach assault went as planned. The water was relatively calm when the 70th Tank Battalion DDs launched 1,500 yards offshore rather than the planned 5,000 yards and puttered to the beach. All but five made it to the sand. Because of the late arrival of the LSTs carrying the DD tanks and the loss of a primary control vessel, Company C’s tanks, which were supposed to land after the DDs of Companies A and B, actually hit the beach first, becoming the assault wave. The company lost four tanks on the way in when the LCT they were on was sunk.

70th Tank Battalion DD tanks assembled on Utah Beach.

70th Tank Battalion DD tanks assembled on Utah Beach.

Little fighting occurred at the water’s edge.[vii] Invading troops encountered only light artillery fire, and by 1000 hours six infantry battalions were ashore.[viii] While Company C tanks took over the mission of suppressing defenses laterally to the left and right of the beach, the DD tanks landed and moved quickly inland to link up with paratroopers of the 101st Airborne Division who had jumped the previous night. The relative ease of the landing was reflected in the fact that as of mid-day, the tanks required no resupply of ammunition. Nevertheless, by day’s end, seven medium tanks had been lost. The light tanks of Company D landed late on D-Day and also joined the 101st Airborne Division. Tankers were “unprepared” for the hedgerow terrain they encountered, but initially faced little resistance beyond shelling and mines.[ix]

*

The 746th Tank Battalion, arriving in landing craft, crossed Utah Beach late in the morning in the second wave, although 1st Platoon of Company A had landed more than two hours earlier in support of the 3d Battalion, 22d Infantry, 4th Infantry Division. Company C, 746th Tank Battalion, formed part of Howell Force, the seaborne component of the 82d Airborne Division, which rolled out of its landing craft about H plus 3 hours. Commanded by Col. Edson Raff, a daring veteran of the North Africa campaign, the force consisted of the 3d Platoon, Troop B, 4th Cavalry Reconnaissance Squadron; ninety riflemen from the 325th Glider Infantry Regiment; and Company C’s medium tanks. Together, they were to drive inland to Ste. Mere-Eglise to link up with the 82d Airborne Division and secure the landing zone for the 325th Glider Infantry Regiment due to land at 2100 hours. Howell Force failed to overcome the 352d Infantry Division’s defenses. The gliders carrying the 325th Glider Infantry swooped in to land as scheduled, and some came down in the German positions. Many others crashed, which resulted in high casualties.

Sherman from the 746th Tank Battalion crosses the beach on 6 June 1944.

Sherman from the 746th Tank Battalion crosses the beach on 6 June 1944.

The Bad News: Omaha Beach

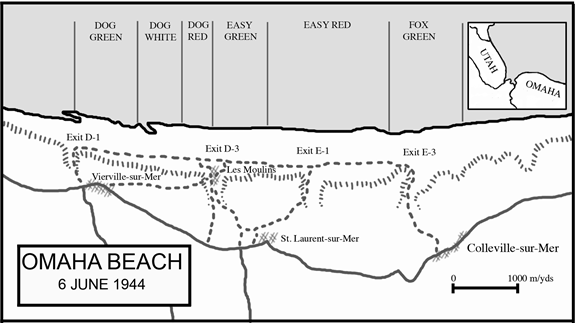

Omaha Beach was about seven thousand yards wide and flanked by cliffs, and defensive obstacles covered the sand. Next came a shingle shelf, which presented a problem for vehicles, and then either a seawall or sand dunes. After a flat, somewhat marshy stretch of ground, bluffs honeycombed with German defensive positions rose 170 feet. A mere four draws offered exits from the beach.[xi]

Off Omaha Beach, winds of ten to eighteen knots caused waves averaging four feet high in the transport area, with occasional waves up to six feet. Breakers were three to four feet.[xii] The DD rigging provided about three feet of freeboard.

At approximately H minus 60 minutes, LCTs bearing DDs of Companies B and C, 741st Tank Battalion, attached to the 1st Division’s 16th Infantry, reached position about six thousand yards from the regiment’s zone at the left end of Omaha Beach. In view of the rough weather forecast for D-Day, the commanding general of Task Force O and the admiral commanding Force O Naval had agreed that the senior naval commander in each LCT flotilla carrying DD tanks would decide whether to launch them at sea or carry them to the beach; the senior DD tank unit commander was to advise the flotilla commander on the matter.[xiii] Captain James Thornton Jr., commanding Company B, was able to reach his counterpart from Company C, Capt. Charles Young, by radio. The two discussed the advisability of launching the DD Shermans in the extremely rough seas—much rougher than any they had tackled during preparatory training. The officers agreed that the advantage to be gained by launching the tanks justified the risk, and they issued orders for launching at approximately H minus 50.[xiv]

The DD tanks began to suffer damage after only a few yards; struts snapped and canvas tore, and water eventually flooded engine compartments. Of the Company B DD tanks launched, only two survived the full distance to Omaha Beach. The rest of Company B and all of Company C sank at distances from one thousand to five thousand yards from shore.[xv]

Staff Sergeant Turner Sheppard commanded one of the two tanks that reached shore. When the tracks hit sand, he told his driver to keep moving forward. It was smoothest landing the crew had ever managed. He deflated the screen, and only then climbed from the deck into the comparative safety of the turret. To his left, he could see the other surviving DD Sherman commanded by Sergeant Geddes on the sand.

Sheppard’s gunner fired at bunkers and pillboxes. Two concrete-piercing rounds slammed into the mouth of a tunnel and produced a satisfying secondary explosion, evidently from the ammunition reserve for a nearby 88mm gun.[xvi]

Three other DD tanks aboard one landing craft were carried all the way to the beach after a wave sank the first DD to exit the vessel and smashed the remaining tanks together, which damaged their screens. Sergeant Paul Ragan, the senior tanker on board, convinced the skipper to take the remaining Shermans to the beach.[xvii]

A knocked-out DD tank, probably on Omaha Beach.

A knocked-out DD tank, probably on Omaha Beach.

“When we drove off the LCT,” recalled Ragan, “I couldn’t see much in front of me except smoke, but there was a clear spot in it, and through here I could see a pillbox. We fired at least forty rounds of 75 ammo at this.” These tanks had landed too far to the right, and they moved left along the beach, weaving past obstacles, skirting a minefield, and firing as they went. Ragan spotted a mortar lobbing shells from behind some drums, and his gunner blew it sky-high. Two of the tanks remained stuck on the beach for seven hours; one pushed ahead to try to knock out a gun but was hit itself and burned.[xviii]

The 1st Infantry Division assault had landed in the teeth of a defense mounted by eight battalions of the well-trained German 352d Infantry Division.[xix] Heavy fire greeted the 16th Infantry’s assault wave, and casualties mounted quickly as the men left their landing craft. The loss of all Company C tanks in the water meant that the GIs on Fox Beach had no armored support at all. The handful of Company B tanks and four boat sections of infantry were the only assault troops on Easy Red Beach for the first half hour of the invasion, and at first, reported some GIs later, the tanks drove up and down the beach but did little shooting.

It all depended where you were. Private First Class Alfred Whitehead II was one of a handful of combat engineers and infantrymen seconded from the 2d Infantry Division to the Special Engineer Task Force for the assault on Easy Red. He recalled, referring to one of the five DD tanks that seemed to him to have appeared from the sea but were already ashore:

I looked around and the picture on the beach was staggering to the imagination. It looked like the end of the world. There were knocked-out German bunkers and pillboxes, cast-off life preservers and lost gas masks, plus piles of all kinds of equipment; wet, waterlogged and ruined. Sherman tanks, halftracks, and other vehicles littered the shoreline, partly submerged and sinking deeper with the rushing tide. More men were still struggling through tremendous forms of twisted steel and shattered concrete, right over broken, lifeless bodies littering the beach—bodies which only a short time before had been living, breathing beings. It was so rough that I thought we had lost the beach three or four times. . . .

For a long time it looked hopeless. The enemy was slaughtering our men with an 88 housed in [a] huge bunker. But just when things looked darkest, one of our Sherman DD amphibious tanks managed to crawl in to the beach and not get knocked-out, probably because there were so many wrecked vehicles the enemy missed spotting it. It moved in close to the bottom of the slope, and I ran over and directed it to that 88. The terrain was such that our tank could creep up close enough to where its gun barrel was just barely sticking its nose over the top of a little rise to fire. I told the tanker that he’d have only a few seconds to move over the rise and shoot, then hit the reverse gears before that 88 could return fire. The first two rounds missed their mark, chipping chunks of concrete outside its massive structure. On the third try the round hit home—right through the bunker’s narrow gun slit.

What a relief![xx]

The tank-dozer platoon of four vehicles and all but three tanks from Company A reached shore in the second wave. The tanks blazed away with their 75mm guns as they neared the beach, although the odds of hitting anything with aimed fire from a pitching landing craft were remote. Nevertheless, one Sherman on a drifting LCT disabled by German fire had the good fortune to destroy with a single 75mm round the artillery piece that had done the damage. Three Shermans went down with an LCT sunk by enemy fire.[xxi]

A tank dozer works the beach in the center of this iconic photo.

A tank dozer works the beach in the center of this iconic photo.

Meanwhile, because the command radio had been ruined by seawater, battalion command personnel had to move from tank to tank to direct fire and move vehicles into more advantageous positions. Both technical sergeants and the radio operator in the group were wounded.[xxii]

By the time the badly shot-up Company L, 16th Infantry, attacked the German strong point assigned to it in a draw through the bluff, two medium tanks were providing covering fire from the beach under the direction of an infantry lieutenant, and the GIs by 0900 captured the objective and moved to the top of the bluff. Likewise, a DD tank appeared at an opportune moment and destroyed several machine guns that were holding up Company F. At about this time, a British destroyer pulled within 400 yards of the sand, and under cover from its broadsides, Company F and the rest of the 3d Battalion were able to reach the crest. We can only imagine the Sherman gunner’s reaction to this display of one-upmanship.[xxiii]

The first tanks crawled off Omaha Beach at about 1700 hours via exit Easy-1, having spent almost twelve hours on that steel-raked sand. Three tanks were knocked out on the road to Colleville-sur-Mer when they tried to exit the beach with the infantry, two of them at the top of the bluff near the 16th Infantry’s CP. Staff Sergeant Turner Sheppard commanded one of them. At the infantry’s request, Sheppard led the way up the road in his DD tank. There was a fortified house at a sharp bend, but the tanks had worked it over fairly well, and Sheppard pulled past it. Suddenly, he spotted an antitank gun in the road about 600 yards away. The German gunners had the drop on him, and their first round penetrated the front armor, killed the bow gunner, and wounded Sheppard. The survivors bailed out. Sheppard was evacuated the next day but returned to the battalion and earned its first battlefield commission.

At 2000 hours, four battalion tanks were still supporting the infantry against machine-gun nests in the vicinity of St. Laurent-sur-Mer. The outfit’s remnants laagered in a field two miles from the water and watched a canopy of red tracers slice the air overhead to drive off Luftwaffe raiders. The battalion’s first daily tank status report, submitted to V Corps at 2315 hours on 6 June, indicated that it had three battle-ready medium tanks, two tanks damaged but reparable, and forty-eight tanks reckoned lost.[xxiv]

*

In the 116th Regimental Combat Team's zone on the right end of Omaha Beach, the officers in charge of the DD tank-loaded LCTs decided not to risk the sea conditions, so all thirty-two DDs of the 743d Tank Battalion were carried nearly to the beach.[xxv] The unit’s S-3 journal recorded: “Company C landed on Dog White and Easy Green beaches at H minus 6 [minutes]. Upon approaching beach we were met with fire from individual weapons, 155mm, 88mm, and machine guns. . . . Air support missing.” Company B landed simultaneously, and Company A’s tanks followed the DDs ashore as planned.[xxvi] Navy navigation errors deposited some of the tanks on beaches intended for use by the 741st Tank Battalion, which was not such a bad outcome, given the losses suffered by that outfit.[xxvii]

The infantry arrived after the tanks. Lieutenant Jack Shea, who landed with the 116th Infantry’s regimental headquarters, recalled,

Our particular LCVP did not draw direct fire until we were within 200 yards of the beach. . . . Moderate small-arms fire was directed at our craft as the ramp was lowered. . . . The first cover available was the partial screen provided by a DD amphibious tank of Company C, 743d Tank Battalion, which had landed at H minus 6. There were about eighteen of these tanks standing just above the water line of Dog Beach. They were faced toward the mainland at an interval of 70-100 yards, and about twenty-five yards from the breakwater. They were firing at enemy positions to their immediate front. Two tanks, near the Vierville exit, had been hit by enemy fire and were burning.

The tank that screened us was firing to its front right, rather than engaging its previously assigned target—the enemy strong point and gun positions atop the cliff at Point et Raz de la Percee. This was necessary for the tank evidently was seeking to protect itself from the fire of several antitank guns that had survived the air-and-naval pre-landing bombardment. . . .

Both [assistant division commander Brig. Gen Norman] Cota and Col. [Charles] Canham expressed the opinion that the fact that these tanks were not firing at Point Percee permitted those enemy gun positions to profitably employ their fires.[xxviii] [Indeed, the German commander of that strong point at first judged that the landing had been crushed on the beach; he saw ten burning tanks and infantry hiding behind obstacles, and he noted that his guns were causing heavy losses.[xxix]]

The tank battalion commander, Lt. Col. John Upham—who had put the battalion together—directed operations from an LCT a few hundred yards offshore until he landed ninety minutes after the assault wave. Upham moved from tank to tank, directing fire and movement. Sometime during the morning, a sniper’s slug destroyed his right shoulder, but he continued to exercise personal leadership until Green Beach was cleared. Only then did he finally allow medics to evacuate him—an action for which he was awarded the Distinguished Service Cross.[xxx]

The sea wall kept the tanks penned on the beach, where Company A lined up along the promenade under fire, two Shermans bursting into flames. The infantry under Cota’s leadership reached the top of the bluff by 1000.

Still lacking tanks, Cota spotted two Shermans from the 741st Tank Battalion headquarters section, which had landed at 1530 and climbed up exit Easy-1 to the bluff, parked next to a hedgerow. Cota commandeered one of them from the 1st Infantry Division and sent it to support his men in St. Laurent-sur-Mer. A sergeant from the 115th Infantry, which had come ashore on the heels of the 116th Infantry, took the assistant driver’s position to guide the driver into position. The tank had just passed between two farm buildings when a high-velocity round whizzed by. Unable to spot the source, the gunner fired ten 75mm rounds and some machine-gun bullets in the direction of the enemy, and the tank backed away.[xxxi]

The first Shermans from the 743d Tank Battalion did not exit the beach until about 2200 hours through exit Dog-1 and moved to a bivouac point about two hundred yards from Vierville. About eighteen DD tanks from Companies B and C got off the beach, as well as half of Company A. The tankers continued to receive sniper and machine-gun fire until dark. The battalion lost sixteen tanks destroyed or disabled during the day.[xxxii] Company A alone had lost eight of sixteen tanks and six dozers; the confusion was such that, at the end of the day, the company commander was not sure how many men had become casualties. Company B had lost seven tanks with three officers and six enlisted men killed in action. Company C was luckier, suffering the loss of only one tank disabled and five men wounded.[xxxiii]

*

The U.S. Army Center of Military History concluded that, regarding the importance of the tanks on the beach that day, “[t]heir achievement cannot be summed up in statistics; the best testimony in their favor is the casual mention in the records of many units, from all parts of the beach, of emplacements neutralized by the supporting fire of tanks. In an interview shortly after the battle, the commander of the 2d Battalion, 116th Infantry, who saw some of the worst fighting on the beach at Les Moulins, expressed as his opinion that the tanks ‘saved the day. They shot the hell out of the Germans, and got the hell shot out of them.’”[xxxiv]

*

Meanwhile, engineers had cut several roads to the top of the bluffs, and landing schedules were adjusted to take advantage of this. The first tanks of the 745th Tank Battalion landed on Fox Green about 1630 and made it to the high ground by 2000, with the loss of three Shermans to mines.[xxxv] Because of the high losses suffered by the 741st Tank Battalion, Maj. Gen. Leonard Gerow, commanding general of Task Force O, decided to commit the 745th Tank Battalion to battle immediately.[xxxvi] (Only one company landed on 6 June, with two more coming ashore on 7 June.)[xxxvii] The arrival of the 745th raised to five the number of separate tank battalions in France by the end of D-Day. The 747th Tank Battalion (in V Corps reserve) would disembark on Omaha at 0700 on 7 June,[xxxviii] and at the height of the Normandy campaign, twenty-one separate tank battalions were employed.[xxxix]

The assault on Omaha had succeeded, but ground units there made less progress than planned. The beachhead was one and a half miles deep at its deepest point. At Utah Beach, in contrast, casualties had been low, and the 4th Infantry Division’s 8th Infantry Regiment had advanced all the way to its D-Day objectives.[xl]

[i] Peter Chamberlain and Chris Ellis, (Churchill and Sherman Specials. Windsor, England: Profile Publications Ltd., n.d). (Hereafter Chamberlain and Ellis, Churchill and Sherman Specials.) Memo by Major William Duncan, 743d Tank Battalion: “Results of Training, Tests, and Tactical Operations of DD Tanks at Slapton Sands, Devon, England, During Period 15 March - 30 April 1944,” dated 30 April 1944 and contained in the records of the 753d Tank Battalion.

[ii] “Armor In Operation Neptune (Establishment of Normandy Beachhead).” Committee 10, Officers Advanced Course, The Armored School, 1949. On-line edition posted at Axis History Forum, http://forum.axishistory.com/viewtopic.php?t=51896, as of April 2007. (Hereafter “Armor In Operation Neptune.”)

[iii] Joseph Balkoski, Beyond the Beachhead, The 29th Infantry Division in Normandy (Mechanicsburg, PA: Stackpole Books, 1999), 124.

[iv] Thomas E. Griess, ed., The Second World War: Europe and the Mediterranean, West Point Military History Series (Wayne, N.J.: Avery Publishing Group, Inc., 1984), 295. (Hereafter Griess.)

[v] Griess, p. 295.

[vi] Seventh Army war diary, record group 407, miscellaneous lists, NARA.

[vii] History of the 6th Armored Group. AAR, 70th Tank Battalion. “Armor In Operation Neptune.”

[viii] Griess, p. 296.

[ix] Ibid., 144. “Armor In Operation Neptune.”

[x] Maj. Roland Ruppenthal, American Forces in Action: Utah Beach to Cherbourg (6 June-27 June 1944) (Washington, DC: Center of Military History, United States Army, 1990, online edition at http://www.army.mil/cmh-pg/books/wwii/utah/utah.htm as of June 2006), 53. (Hereafter Ruppenthal.) Maj. Robert Tincher, “Reconnaissance in Normandy—In Support of Airborne Troops,” The Cavalry Journal, January-February 1945, 12.

[xi] Griess, 297.

[xii] Omaha Beachhead (6 June–13 June 1944), American Forces in Action Series, (Washington, D.C.: Center of Military History, 1984), online reprint of CMH Pub 100-1, http://www.army.mil/cmh-pg/books/wwii/100-11/100-11.HTM.), 38. (Hereafter Omaha Beachhead.)

[xiii] AAR, 3d Armored Group.

[xiv] AAR, 741st Tank Battalion; Heintzleman, p. A14.

[xv] Hand-written interviewer notes on reverse of “Company H, 16th Infantry,” Combat Interviews, 1st Infantry Division, NARA.

[xvi] Heintzleman, 28.

[xvii] Interview with Paul Ragan.

[xviii] Hand-written interviewer notes on reverse of “Company H, 16th Infantry,” Combat Interviews, 1st Infantry Division, NARA. Heintzleman, 24-25.

[xix] Griess, 297.

[xx] Alfred II Whitehead, “The Diary of a Soldier,” the Second Infantry Division Photo Web Pages website, http://home.thirdage.com/Military/friends2idww2/Combat_Journal.html as of November 2007. (Hereafter Whitehead.)

[xxi] “16-E on D-Day,” Combat Interviews, 1st Infantry Division, NARA. “Company H, 16th Infantry,” Combat Interviews, 1st Infantry Division, NARA. “Armor In Operation Neptune.”

[xxii] AAR, 741st Tank Battalion.

[xxiii] Ibid. “Armor In Operation Neptune.” “The D-Day Experiences of Company L, 16th Infantry,” Combat Interviews, 1st Infantry Division, NARA. “Company H, 16th Infantry,” Combat Interviews, 1st Infantry Division, NARA. “The Story of Company F, 16th Infantry, on D-Day,” Combat Interviews, 1st Infantry Division, NARA. “Company H, 16th Infantry,” Combat Interviews, 1st Infantry Division, NARA.

[xxiv] Unit Journal, 741st Tank Battalion. Hand-written interviewer notes on reverse of “Company H, 16th Infantry,” Combat Interviews, 1st Infantry Division, NARA. Heintzleman, 25, 28-29.

[xxv] Omaha Beachhead, 39.

[xxvi] AAR, 743d Tank Battalion.

[xxvii] Folkestad, 4.

[xxviii] Account of Lt. Jack Shea, Combat Interviews, 29th Infantry Division, NARA. (Hereafter Shea.)

[xxix] Gordon A. Harrison, Cross-Channel Attack: United States Army in World War II, The European Theater of Operations (Washington, D.C.: Center of Military History, 2002), 319-320. (Hereafter Harrison.)

[xxx] Robinson, 26–27.

[xxxi] Shea. Journal, 741st Tank Battalion.

[xxxii] S-3 Journal, 743d Tank Battalion. Interview with Capt. Joseph Ondre, Combat Interviews, 29th Infantry Division, NARA.

[xxxiii] S-3 Journal, 743d Tank Battalion.

[xxxiv] Omaha Beachhead, 81.

[xxxv] Omaha Beachhead, 107–108.

[xxxvi] AAR, 3d Armored Group.

[xxxvii] AAR, 745th Tank Battalion.

[xxxviii] AAR, 747th Tank Battalion.

[xxxix] Sawicki, 22.

[xl] Ruppenthal, 53.