For part two of his three-part overview of US Army amphibious operations in Western Europe, I again hand the keyboard over to Harry Yeide. - The Cheiftain

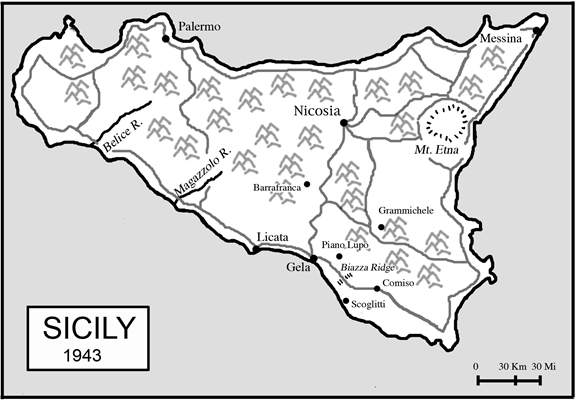

Sicily: Operation Husky

The Allied landings on 10 July 1943 constituted the largest amphibious assault of the war and put seven divisions ashore in Sicily. In the American zone, Combat Command A, 2d Armored Division, landed at Licata to support the 3d Infantry Division’s beachhead on the left of the American assault zone, while the 753d Tank Battalion (Medium) supported the 45th Infantry Division on the right around Scoglitti. Ten of the 753d Battalion’s Shermans were to help the 1st Infantry Division in the center around Gela until Combat Command B, 2d Armored Division, and the 70th Tank Battalion (Light) came ashore. The two combat commands were initially to fill the role normally accorded separate battalions: Infantry support.

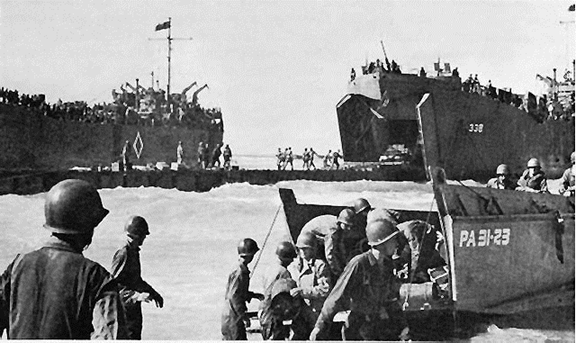

The invasion fleet was equipped with new models of landing vessels that were designed to speed the delivery of vehicles and men to a hostile shore. The Landing Ship, Tank (LST); Landing Craft, Tank (LCT); Landing Craft, Infantry (LCI); and Landing Craft, Vehicle or Personnel (LCVP) saw action for the first time. No longer would tanks have to be hoisted over the sides of transports into landing craft; now, they would arrive off the invasion coast aboard their ride to the beach.

LSTs offload vehicles across pontoons on Sicily.

LSTs offload vehicles across pontoons on Sicily.

The potential revolution of delivering tanks to a spot nearly on the sand did not fully pan out at Sicily, however. False beaches or sandbars off the selected landing areas gave way to fairly deep water before the true shore. As a result, pontoons had to be used between an LST’s bow doors and the beach as during the Oran landings—though this time they were prefabricated for speedy installation—or a cumbersome LCT relay employed.[i] Moreover, there were not enough of the new craft to equip the entire force. The 45th Infantry Division arrived combat loaded from the States in traditional fashion. As had inexperienced divisions and fleets thus equipped at Torch, the landing force suffered high losses in landing craft—up to fifty percent off some transports, and twenty percent overall.[ii] The bulk of the 1st Infantry Division’s vehicles arrived aboard transports from North Africa. Only the 3d Infantry Division (code-named Joss Force) received enough landing craft to mount a shore-to-shore operation from North African ports.[iii]

Yet, despite the success in landing some light tanks with the assault wave during Operation Torch and the availability of LCTs to Joss Force, for unknown reasons no tanks were assigned to the assault wave in Operation Husky. The assault force commanders imposed a set of rules that applied to all regimental combat teams landing on all beaches, which included several stipulations regarding tanks. The first wave of LCTs was not to hit the beach until H plus 90 minutes (with one exception), and five of those were to carry medium tanks towing antitank guns and followed by the latter’s prime movers. All LCTs were to be loaded to permit tanks to fire as they approached the shore. All transports were to be tactically loaded, with no more than one tank company on any given vessel.[iv]

Major General Lucian Truscott, commanding the 3d Infantry Division, evidently was the one exception. Truscott assigned the 3d Battalion, 66th Armored Regiment, to land one company of medium tanks by LCT immediately behind the last battalion of each infantry regiment, which would put tanks on the island within 60 minutes of H-Hour. The remainder of Combat Command A was to remain in floating reserve and land on call.[v]

It is unclear how far behind the 45th Division’s assault wave the 753d Tank Battalion landed, but it went ashore with the 157th Infantry. The tank battalion’s records for Husky are missing. As of midnight on D-day, the division G-3 was unaware of any action involving the tanks, and the tanks’ presence is first reflected in 45th Division message traffic about combat operations on D plus 1.[vi]

*

The naval bombardment began only fifteen minutes before the assault boats reached the sand because Lt. Gen. George S. Patton, commanding the American force, wanted to achieve tactical surprise.[vii] Indeed, even though the Italian coastal defenses had an hour’s tactical warning because of airborne drops inland, the 1st and 3d Infantry divisions rolled ashore against virtually no opposition.

The 45th Division landed three regiments abreast with destroyers providing the close support against targets on the beach that tanks might otherwise have. The tin cans followed the assault troops to within 3,000 yards of the beach, blazing away. “Sometimes,” recalled Maj. Ellsworth Cundiff, S-2 for the 179th Infantry in the division’s central zone, “it seemed as if the destroyers themselves were making the assault.”

The GIs paid the price for not having tanks sent in with them. Resistance on the beaches in the 45th Division’s zone ranged from spirited in the 180th Infantry’s area to nothing elsewhere. Once the regiments moved toward their objectives inland, a combat group from the Hermann Göring Panzer Division consisting of Mark IV and Mark VI panzers, infantry, and artillery, badly mauled the 1st Battalion, 180th Infantry, pushed the regiment back, and created a potentially dangerous gap between it and the 179th Infantry, which was advancing on the Comiso airfield.[viii]

At Gela, two Ranger battalions attached to the 1st Infantry Division without any armor support fought off Italian counterattacks backed by tanks. At Piano Lupo crossroads, 82d Airborne Division paratroopers and the first advancing doughboys from the 1st Division’s 16th Infantry needed naval gunfire to beat back Italian tanks, and then much of the Hermann Göring Panzer Division.[ix]

A 2d Armored Division tank plows its way up Sicilian beach just after leaving the LCT that landed it, 10 July 1943.

A 2d Armored Division tank plows its way up Sicilian beach just after leaving the LCT that landed it, 10 July 1943.

The Axis the following day threw more tank-heavy counterpunches at the American beachhead, and the slow arrival of friendly armor almost had fatal consequences for the 1st Infantry Division. Two CCB tank platoons had landed late on D-day but got stuck in soft sand. Four Shermans got loose on D plus 1 in time to help fend off a large armored attack that nearly overran the 1st Division’s beaches.

That same day, two platoons of Company B, 753d Tank Battalion, came to the aid of 82d Airborne Division paratroopers near Piano Lupo, but only after their epic close-range fight against counterattacking Tigers from the Hermann Göring Panzer Division at Biazza Ridge. The tankers supported an evening attack against the Germans and claimed the destruction of a Tiger and a Mark IV, two 88s, and five machine-gun emplacements while losing four Shermans.

Tank support was finally playing a role in the 45th Division’s zone, where the 157th Infantry ordered Company C, 753d Tank Battalion, to seize Comiso airfield and hold it until the arrival of the infantry—an order that reflects no grasp of combined-arms tactics. The tankers moved out, company commander Capt. George Fowler’s Sherman in the lead. After crossing a ridge west of Comiso, Fowler spotted five Italian Renault tanks, which he engaged at only 200 yards. 75mm rounds ripped through the light armor and destroyed all five tanks in short order. The regiment had overrun the airfield by evening.[x]

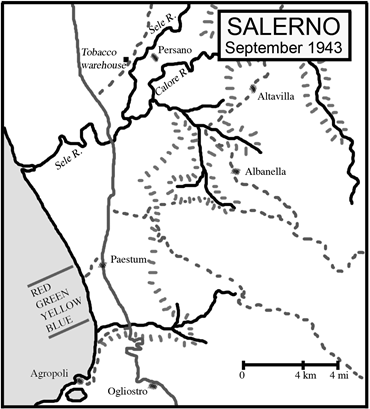

Italy: Operation Avalanche

Lieutenant General Mark Clark’s Fifth Army was a showcase of Anglo-American integration. It included two corps, Maj. Gen. Ernest Dawley’s U.S. VI Corps and Lt. Gen. Sir Richard McCreery’s British 10 Corps, and, along with the British Eighth Army, was part of the 15th Army Group, commanded by Gen. Sir Harold Alexander. Both corps participated in Avalanche, the British landing to the north of the Americans. By the time Allied troops set foot on Italy, the capture of Sicily had already effectively cleared the Germans from the Mediterranean, and the theater had become a subsidiary one to the great invasion being planned for France.

Decision-making by commanders regarding the use of armor in Italy appears to have been unusually bad, starting with a failure to provide adequate armored support to the assault force at Salerno. The 36th Infantry Division, a green outfit fresh from the States, was to conduct the landing. Follow-on troops were to include the 45th Infantry Division, one reinforced regiment of which was in floating reserve; the 3d and 34th Infantry divisions; and the 1st or 2d Armored Division. The 82d Airborne Division stood ready on Sicily if needed. Allied intelligence assessed that the Germans had a panzer division in the vicinity of Salerno, and that the landing force could expect to encounter panzers early.[xi]

The first American tanks were not even scheduled to land until the sixth wave—or H-hour plus 140 minutes. According to the plan, the 751st Tank Battalion (Medium) was to put a single platoon ashore before daybreak with each of the 141st and 142d Infantry regiments. Company A’s 1st Platoon, assigned to the 141st Infantry, was to support a “flying column” that was to enter the village of Agropoli. The remaining combat elements of the battalion were to land throughout D-day. Major General Fred Walker, commanding the 36th Division, believed that this timetable would get tanks ashore in time to deal with any armored counterattack, though his total armored strength at first light was to be only ten medium tanks.

The first tank destroyers, roughly two companies of M10s from the 601st Tank Destroyer Battalion—which according to doctrine were actually supposed to fight tanks—were not to land until 1630, thirteen hours after the first GIs. This was better than the initial plan, which foresaw no tank destroyers arriving until D plus 2. To cap Salerno’s status as the antithesis of amphibious warfare doctrine, Walker decided to forego a preliminary naval bombardment and indeed hoped the shelling of the British beaches would draw off any panzer units in his area.[xii]

Why planners for Operation Avalanche strayed so far from the emerging amphibious doctrine—shell the beach, storm the beach (with armor along to protect the infantry), secure the beach—is a mystery. The assaulting division’s commander exercised his judgment regarding the bombardment. Who scheduled the belated arrival of armor is less clear. The Salerno beaches were optimal for landing craft up to the size of LSTs, the exits were suitable for tanks and vehicles, and the only known obstacle was an antitank ditch behind the beach. Other nearby beaches were appropriate for tanks, although some were defended by pillboxes.[xiii] Fifteen LSTs were available for the landings, and Clark had demanded an increase from the three initially allocated in part to land tanks and tank destroyers.[xiv]

*

The 16th Panzer Division, which defended the landing area, received warning a day before the invasion that an Allied fleet had sailed from Sicily for Salerno, and it was put on alert. At 1600 hours, its status was raised to “ready for battle.” Warning orders had also reached other panzer and panzergrenadier divisions south of Rome. As the Fifth Army history records, once the landings began, “German motors began to roar, and column upon column swung out onto the roads of Southern Italy, driving rapidly [toward] the plains of Salerno.”[xv]

*

At one minute after midnight on 9 September, riflemen of the 141st and 142d Infantry regiments clambered down rope nets from troop transports 12 miles off shore into waiting landing craft. Stubby landing craft prows turned toward Italy, and at 0330 hours the initial wave hit the beach. Miraculously, all was quiet. The rumble and flashes of gun and rocket fire to the north, where two divisions of the British 10 Corps were conducting their assault closer to Naples, told a different story.

As the first squads pushed inland, a loudspeaker called out in English, “Come on in and give up. We have you covered!” Suddenly, German flares popped in the night sky. A furious rain of mortar and machine-gun rounds struck the men now crossing the beach. The infantry assaulted German positions among the dunes, and by dawn, most units were approaching their initial objectives.

Shortly after daybreak, the first two company-sized German tank groups counterattacked. One, striking from the south, overran assault troops of the 142d Infantry and sewed confusion. The second group appeared to the front of the 141st Infantry and kept the men pinned down much of the day. A third tank attack at 1020 was stopped only one half mile from Paestum on the sea by field pieces firing over open sights and 37mm guns on weapons carriers manned by the 36th Cavalry Reconnaissance Troop. More panzer attacks followed, and the GIs held them off with bazookas, grenades, and supporting naval gunfire.[xvi]

Tanks from the 191st or 751st Tank Battalion debark across a pontoon from an LST at Salerno on 9 September 1943. This method was slow and vulnerable to enemy fire.

Tanks from the 191st or 751st Tank Battalion debark across a pontoon from an LST at Salerno on 9 September 1943. This method was slow and vulnerable to enemy fire.

The rate at which American tanks were reaching shore, meanwhile, was falling far short of even modest plans. The Landing Craft, Mechanized (LCMs), carrying the 1st Platoon, Company A, 751st Tank Battalion, twice tried to reach Blue Beach and failed for reasons that are not clear. One tank finally managed to land at 1500 hours, and the remaining four did not arrive until 1730 across a different beach.

The 2d Platoon beat the designated assault platoon to the beach, but it, too, arrived piecemeal. One tank landed at 0800, followed by a second at 1000, and a third at 1100. A general officer commandeered the second of the tanks to use as his transportation, but the other two went into action with infantry working toward Yellow Beach. The rest of the platoon did not get to Italy until the next day.

The 3d Platoon got its first tank to the beach at 0930, and Sgt. Thomas Glasheen moved smartly inland to support the doughboys. He soon found that the Germans were already counterattacking, and his gunner knocked out two Mark IV Specials (equipped with a long-barreled 75mm gun) and an antitank gun. As Glasheen’s tank approached the main highway, a high-velocity round penetrated the turret, killed the gunner, and wounded the rest of the crew.

The platoon’s second tank did not arrive until 1330, and the remainder after nightfall. Because of an insufficient number of landing barges, Company B did not start landing until afternoon, followed by Company C and other battalion elements.[xvii]

The 191st Tank Battalion was having no better luck. The battalion’s intended lead elements, including the command tank, reconnaissance platoon, assault gun platoon, and Company A, had sailed from North Africa aboard LCTs, while the remainder of the outfit followed in two LSTs. The LCTs had arrived at 0330 and been guided through a minefield into Salerno Bay. The LCTs headed for the beach around 0600 hours and immediately drew German artillery fire. Three LCTs were driven back by fire twice before putting two platoons of tanks and the assault guns ashore at 1130, one vessel listing and with wounded on board. Immediately on landing, an unknown general ordered the 3d Platoon to secure some high ground near the beach and prepare to fend off an expected panzer attack.

A shell struck the ramp of a fourth LCT, and then a second round hit a tank, glanced off, and exploded in the pilothouse, where it killed a naval officer and an entire gun crew. The LCT, only 600 yards from shore, turned to head back to sea, and a third round penetrated the side of a tank, killed two men, and set the Sherman alight. With great difficulty, the smoldering tank was pushed off the damaged ramp into the water. This LCT began to take on water and does not appear to have reached the beach. The remaining two reached shore at 1345 and 1540 hours, respectively, each on its third attempt.

The LSTs experienced difficulties, as well. One lowered its pontoon well out to sea at 1030 and headed in. About a mile from shore, it was struck twice by guns located near Paestum, and several men on the pontoon were wounded. Debarkation began at 1505 under intense artillery fire. The second LST failed two times to reach its assigned beach and was sent to another, were the tanks off-loaded at 1530 with nary a friendly GI to be seen. There were some Germans, but they took off when the tanks appeared.

The tankers de-waterproofed their vehicles under artillery fire and strafing from German fighters. The exhaust and intake shrouds on most tanks had to be pulled off by other tanks or hacked free with axes. They had been designed to fit the M10 tank destroyer, but that was what the Army had provided.

The battalion rallied, and led by Company C, drove westward to the Sele River, where the Germans destroyed the bridge as the tanks appeared. The battalion’s after-action report records that in the course of the afternoon, it knocked out at least eight Mark IV tanks, four antitank guns, a pillbox, and an unknown number of infantry while losing not a man or vehicle. “It is apparent that the defense of the highway from Paestum to the Sele bridge was not too carefully planned,” wrote the recording officer. “The enemy withdrawal was not an orderly one.”[xviii]

By day’s end, Allied units had reached their D-day goals with the exception of most of the 141st Infantry Regiment. The next day, VI Corps experienced almost no opposition as the 143d Infantry landed, and the 36th Division occupied positions in the hills overlooking the beachhead.[xix] Doubtless stung by the preceding day’s events, the 36th Infantry Division employed its armored strike force in a most peculiar fashion. Companies B and C, 751st Tank Battalion, were ordered to take up defensive positions on either side of the main highway to defend against any armored attack from the south. The Company C tanks fired artillery missions from their positions near the road.[xx]

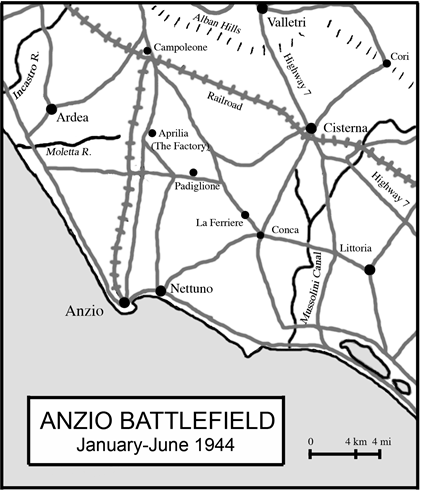

Anzio: Operation Shingle

The VI Corps amphibiuous assault at Anzio on 22 January 1944 showed that the Army had learned some hard lessons in the preceding two landings, and this time the first tank landed only 40 minutes after the first rifleman. All of the beaches in the American zone would require engineering work, such as laying steel mats, to get armored vehicles inland. A sandbar offshore blocked access by LSTs, which would demand use of pontoons.[xxi] The lessons of Salerno evidently were fresh enough that this time ways were found to get the infantry tank support from the start using LCTs, which could land at spots.

H-hour was 0200 hours on 22 January, the amphibious operation was picture-perfect, and the assault troops were astonished to find that there was no enemy to meet them—the operation had caught the Germans completely by surprise. A few antiaircraft batteries on the coast fired several rounds, but only two battered battalions from the 29th Panzergrenadier Division were anywhere near Anzio.[xxii] By 0240, the 751st Tank Battalion had its Company A on land, with a platoon moving to support each of the three regimental combat teams of the 3d Division. Resistance, as it turned out, was virtually nonexistent off the beach, as well, and the infantry quickly occupied its initial objectives and dug in against counterattack. Company B and the mortar platoon were ashore by 0700, and the rest of the battalion shortly after noon.[xxiii]

Tanks disembark at Anzio.

Tanks disembark at Anzio.

The first tank-backed patrols from the Hermann Göring Panzer Division, rushing to contain the landing zone, appeared at the Mussolini Canal at about 1800 hours but were driven off, and the American tankers worked with the GIs against German infantry elements through 24 January.

[i] Lt. Col. Albert N. Garland, Howard McGaw Smyth, and Martin Blumenson, Sicily and the Surrender of Italy: United States Army in World War II, The Mediterranean Theater of Operations (Washington, DC: Center of Military History, 1993), 104-105. (Hereafter Garland, et al.)

[ii] The Historical Board, The Fighting Forty-Fifth: The Combat Report of an Infantry Division (Baton Rouge, Louisiana: Army & Navy Publishing Company, 1946), 17. (Hereafter The Fighting Forty-Fifth.)

[iii] Truscott, 196.

[iv] C.O.H.Q. Bulletin no. Y/1, “Notes on the Planning and Assault Phases of the Sicilian Campaign by a Military Observer,” October 1943.

[v] Truscott, 198.

[vi] Journal, 45th Infantry Division. Journal, II Corps.

[vii] Rick Atkinson, The Day of Battle (New York: Henry Holt and Company, LLC, 2002), 60.

[viii] Maj. Ellsworth Cundiff, “The Operations of the 3d Battalion, 179th Infantry (45th Infantry Division) 13-14 July 1943 South of Grammicele, Sicily (Personal Experience of a Regimental S-2),” submitted for the Advanced Infantry Officers Course, 1947-1948, the Infantry School, Fort Benning, Georgia. (Hereafter Cundiff.)

[ix] Sicily, 10-11.

[x] The Fighting Forty-Fifth, 21.

[xi] “Outline Plan—Operation Avalanche,” G-2 assessment, 21 August 1944, Fifth Army records. History, Fifth Army. Blumenson, Salerno to Cassino, 49.

[xii] AAR, 751st Tank Battalion. “Outline Plan—Operation Avalanche, A-Allotment of Shipping,” Fifth Army records. “Report of Observation Trip, NATO,” Maj. Gen. W. H. H. Morris, Jr., 27 November 1943, General Staff G-2 Section Intelligence Reports, Numerical File, 1943-46, folder 57, NARA. Operations report, 601st Tank Destroyer Battalion. Blumenson, Salerno to Cassino, 56-57.

[xiii] Western Naval Task Force, Operation Plan No. 7-43, Short Title “AVON/W1.” “Outline Plan—Operation Avalanche,” Fifth Army records.

[xiv] History, Fifth Army.

[xv] History, Fifth Army.

[xvi] Ibid. Blumenson, Salerno to Cassino, 73-77.

[xvii] AAR, 751st Tank Battalion.

[xviii] History and AAR, 191st Tank Battalion.

[xix] History, Fifth Army.

[xx] AAR, 751st Tank Battalion.

[xxi] “Shingle Intelligence Summary No. 8,” Headquarters, Fifth Army, 11 January 1944

[xxii] History, Fifth Army.

[xxiii] AAR, 751st Tank Battalion.