The ever-popular Harry Yeide is back! This week, he's taking a look at the development of the US Army's doctrine for using tanks in built-up areas. Over you you, Mr Yeide! - The Chieftain

US Army Tanks in the Cities in World War II

The US Army had a mere stub of a doctrine for using tanks in cities when it entered the war. The 1942 field manual for armored units on tactics and technique (FM 17-10) emphasized “the grouping of overpowering masses of armored units and launching them against vital objectives deep in the hostile rear. . . . The attack of armored force units should be characterized by boldness and speed in striking sudden blows in the most favorable direction.” The first mention of urban warfare was the admonition, “Armored units avoid defended towns or cities when possible except when they can be surprised. Such localities are attacked by motorized infantry or other closely following troops.”[i]

The entire body of doctrine was as follows:

Combat In Towns

a. General. In general, armored vehicles are not suitable for combat in towns, particularly large towns. Towns offer concealment to large forces, observation is limited, fire effect is reduced, and combat deteriorates to that of small groups. Such localities enable the enemy to effectively use antitank weapons, barricades, demolitions, and mines.

b. Attack of a town. Armored units, if practicable, avoid attacking towns. If attack must be made, the town is encircled. A direct frontal attack is resorted to only when encirclement is impossible.

(1) Attack by encirclement. The support echelon with part of the artillery makes the direct assault on the town while tank units move around one or both flanks to cut off the forces in the town from reinforcements and isolate it from hostile supporting forces. When no infantry is present, part of the tank units, supported by machine gun elements, is used for the main attack.

(2) Frontal attack. This form of attack is resorted to only as a last resort or when the locality can be surprised. The Infantry supported by all the artillery makes the attack. Tank destroyer and tank units will usually be used only to repel counterattacks after the town has been taken. When no Infantry is available, elements of the reconnaissance and battalion headquarters companies may be used in the assault, while tank and artillery units cover the advance by fire. (See FM 7-5.)

c. Defense of town. In defense of a town, infantry supported by artillery and tank destroyer units are used to defend the town itself, while tank units are held in reserve to attack enveloping forces. When a tank unit is acting alone, it uses its mobility to attack the enemy before he reaches the outskirts. (See FM 7-40.)[ii]

Woe betide the tank commander who actually had to fight in a town, an operation he and the infantry would never have learned together. Stateside armored training did not even include the use of tanks in towns.[iii]

This article will examine the largest-scale American uses of tanks in urban combat in Italy, Germany, and the Philippines.

North Africa: Urban Warfare Bookends

American tankers saw almost no urban combat in North Africa, and what little there was occurred at the very beginning and end of the campaign. Indeed, the issue arose on the very first day of Operation Torch, the Allied landings in North Africa on 8 November 1942. I covered the experience of the street fighting of 2d Platoon, Company A, 756th Tank Battalion at Fedala, Morocco, in an earlier edition of the The Chieftain's Hatch.

The second occasion was when the 751st Tank Battalion saw action with the 9th Infantry Division, to which Company A was attached on 4 May, during the II Corps’ drive on Bizerte, Algeria. The 9th Division had not worked with infantry-support tanks since the Torch landings, and it showed. On 7 May shortly before noon, the tankers along with the 894th Tank Destroyer Battalion were given the mission to reconnoiter some hills to the east and north and “overcome any opposition found therein.” Sending armor alone off on such a mission showed no grasp of combined-arms operations.

The 9th Division again ordered the armor to advance alone into Bizerte, which the vehicles entered about 1550 hours—the first Allied troops to enter the town. Major General Manton Eddy, the 9th Division commanding general, gave an attached French brigade the honor of sending the first foot soldiers into Bizerte, and photographic evidence indicates that the tanks helped the infantry root out a few die-hard defenders. The tanks withdrew that night because they had attracted artillery fire.[iv]

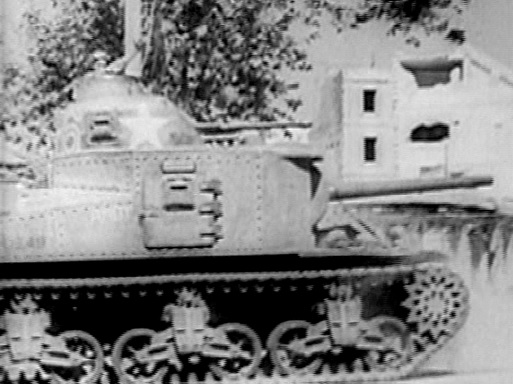

An M3 medium tank belonging to Company A, 751st Tank Battalion (Medium), engages in street fighting in Bizerte, Tunisia, on 8 May 1943. (Signal Corps film)

An M3 medium tank belonging to Company A, 751st Tank Battalion (Medium), engages in street fighting in Bizerte, Tunisia, on 8 May 1943. (Signal Corps film)

Italy: The First Big City Fight

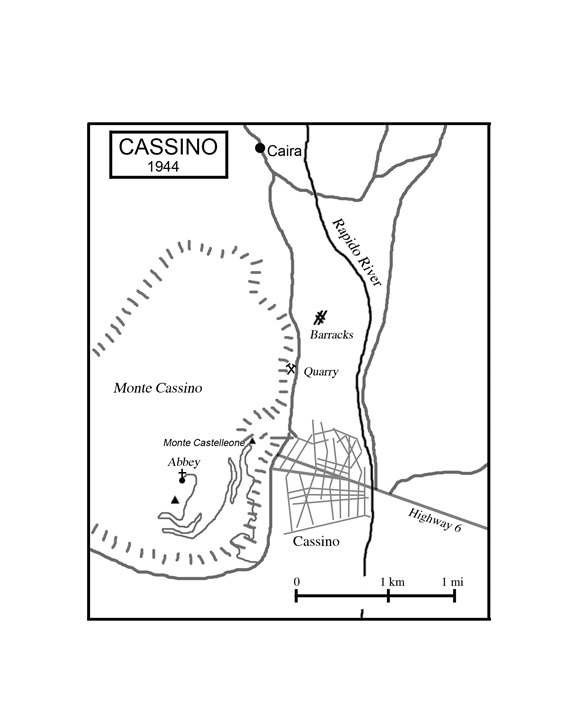

The town of Cassino and the mountain that towered above it with its famous Benedictine abbey was the linchpin of the Gustav Line. It was also by far the best-fortified town Fifth Army had encountered to date, or would face thereafter. The 34th Division’s ultimately fruitless struggle to capture the town alongside the 756th Tank Battalion took place on a crazy-quilt battlefield that favored an enemy adept at using his own tanks, infantry, and artillery in sweet harmony. It stands as a superb illustration of how American infantry and tankers learned to cooperate under fire, with both flashes of brilliance and breakdowns in teamwork, and embodies about the best case one could hope for as long as the two elements of the team had no good way to communicate directly at the tactical level.

The 756th Tank Battalion’s first fire missions in the sector were actually conducted to support the neighboring 36th Infantry Division during its attempt to force the Rapido River line on 20 January. Medium tanks fired indirectly as artillery, and the battalion consolidated its six assault guns into an artillery battery. As in the Pacific, assault gun crews suffered considerably from the build-up of gun fumes in the tank. “Sometimes [the crews] would get sick and have to stop and vomit during the heavy firing on account of the gasses from the powder smoke,” recalled Roy Collins. “They’d bail out of the tank, vomit, and climb right back in and continue firing.”[v]

The 34th Division was to cross the Rapido north of the town of Cassino, capture Monte Castelleone, and then take Monte Cassino from the rear.

Cassino was the American tanker’s first experience in serious urban fighting. The 756th Tank Battalion, fighting with the 34th Infantry Division, on 2 February 1944 became the first Allied unit to enter Cassino. The battalion employed a composite company of the running tanks from the three medium companies in what was initially a well-coordinated operation with the 3d Battalion, 133d Infantry Regiment. Lieutenant David Redle commanded the tank force and was given charge of the mortar and assault gun platoons, which were to provide smoke and supporting fire. Artillery provided a smokescreen for the command when it moved out southward along the Rapido River, the infantry sticking close to the tanks.

At 0730, the 3d Battalion reported to Regiment, “We jumped off. The tanks are moving up with us.”

“Keep your men off the road for the tanks. Are the tanks firing?”

“Yes, sir.”

The force advanced in bounds, placing smoke 300 yards ahead, clearing the area, and repeating the procedure. The tanks advanced some 500 yards without contact until Germans in a bunker just beside the road threw some hand grenades. Redle’s gunner took care of the problem, but Redle guessed that they had bypassed other camouflaged field works. Redle backed the column up and started again. Sure enough, this time the Americans flushed out some 150 German soldiers.

Whenever a machine gun opened fire on the GIs, the tanks dealt with it. The force reached a stream about four feet deep, and engineers moved in to construct a tank crossing. When the infantry moved a bit ahead of the tanks, Redle ordered his crews to fire only machine guns and solid-shot AP to avoid causing friendly casualties.

M4 tank number C-14 (from the 3rd Platoon of "C" Company) stuck in the mud near the Rapido River north of Cassino on 8 February 1944. (Source: The 756th Tank Battalion)

As the tanks neared Cassino, they became channeled onto narrow paths, one along a blacktop road between the high bank of the Rapido River and the slope of Monte Cassino, and the other in the riverbed, so that only the front vehicles were able to fire. This became a problem when the smoke dissipated, and at about 1100 hours accurate fire screamed in from a camouflaged self-propelled gun in hull defilade on the outskirts of Cassino. The SP gun shot the turret hatch off the M4A1 in the riverbed and wounded the commander. A second shot passed so close to Redle’s head in the lead tank on the road that he was deafened in one ear for hours. Redle’s tanks backed into a quarry for protection, and the infantry’s attempts to knock the gun out with artillery and mortar fire were fruitless.

At 1630 hours, battalion CO Lt. Col. Harry Sweeting instructed that the 34th Division was going to fire a heavy barrage at Cassino, and he ordered the reserve force—four or five Company A Shermans—into town. At this point, coordination with the infantry broke down because the infantry officers had gone back several hundred yards to their battalion CP for orders, and Company K had pulled back to an assembly area. Moreover, the Company A tank platoon commander’s radio was on the fritz. The tanks charged alone into Cassino, where the Germans—who had been ordered to withdraw until their officers realized the tanks had no infantry support—waited in ambush.

Point-blank fire destroyed the last tank in line, and the remainder were trapped. The tanks sought a way out, and the Germans pursued them with bazookas, grenades, and dynamite. Three or four antitank rounds slammed into one tank but did not penetrate the armor. Close assault by infantry claimed one after the other, however. Redle was ordered to pull back because of advancing darkness, and he directed his driver to town to pass the order personally because of the radio problem. All he found was an empty tank from Company A.

The next morning, a company of medium tanks from the 760th Tank Battalion was attached to the 756th Battalion to reinforce its striking power after its heavy losses. Major Welborn Dolvin, the executive officer, commanded the tank force assigned to enter Cassino alongside the 3d Battalion, 133d Infantry Regiment. Dolvin’s tank took a high-velocity round in the final drive and burst into flames. Dolvin bailed out and sprinted to Redle’s tank, which had a radio on the battalion net, and directed the attack from the back deck.

“What’s holding you up?” queried Sweeting over the radio.

Dolvin looked around. “I don’t know, Colonel, but I think it’s the Germans.”

Another artillery barrage fell on Cassino, and the 760th Tank Battalion’s Company C and the infantry tried again. Lieutenant Leo Trahan’s 2d Platoon, followed by about fifty infantry, managed to capture the first four or five buildings in Cassino, and after some confusion between the tankers and infantry that nearly resulted in a withdrawal, the team got its act together and settled in to protect one another. Trahan’s tank was hit and burned during the aborted withdrawal, and a second tank became immobilized. Joined by other Company C tanks, the men from the 760th slugged it out in the streets of Cassino beside the tankers of the 756th Battalion until 7 February, when the detached company returned to its parent battalion.

For the next month, the medium-tank companies in the 756th Tank Battalion each kept a platoon—which by now usually meant no more than three tanks—in Cassino to work with the infantry. The GIs attacked mainly at night because German observation was so good that any movement drew heavy fire during the day. The tankers’ main job was to blast holes in the walls of fortified buildings that the riflemen could pass through, and gunners made heavy use of concrete-piercing ammunition.

Advances were measured in tens of yards, and tankers learned that working with the infantry in the confusing urban battlefield could be tough. Lieutenant Howard Harley lost his tank to bazooka fire on 12 February and later related, “It was because the fight was so wild that we got ahead of the infantry. You get lost in your intent sometimes and pursue targets with intent so strong you can get up ahead without realizing it.”[vi]

A British observer who witnessed the Cassino operation commented, “In the initial advance, the tanks work in mutual support. Once inside the town, however, it becomes a personal matter, and each tank must fend for itself. . . . An enemy behind solid walls is difficult to dislodge. . . . By continuous firing at heavily fortified buildings, and chipping a few inches with each shot, the 75mm HE shell with a delayed-action fuse has finally reduced the strongest building. . . . There have been many occasions when, at the request of the infantry, close tank support has been given from the immediate vicinity of the forward troops; each support naturally increases the danger to the tank. Casualties to crews have been caused by the penetration of enemy rifle grenades and [antitank] bombs of the rocket type fired on the upper surfaces of the tank from upstairs windows. . . . During a sortie, as many as 200 shells have been directed against [the tanks] in town. Despite this, the infantry still prefer to have them in close proximity.”

Sweeting told the observer that his use of tanks as close as five yards to the infantry was “an improvised use. . . which should not become a habit.” The British officer noted that the Germans used their self-propelled guns aggressively in the town’s streets—they would advance to point-blank range, fire, and withdraw—and that chance engagements with American tanks were frequent. There were few long streets, and local commanders had to designate streets for use by friendly tanks—any other vehicular movement was met immediately by fire. The Germans generally used their Mark IV tanks outside the town but occasionally employed them much as the Americans used their Shermans.[vii]

Redle described one such encounter, when Sgt. Haskell Oliver’s tank was crossing a street to knock holes in the wall of a building near the town jail. A ball of fire streaked past the nose of the tank, and Oliver backed off. Sweeting was in a nearby observation post and reported that a Mark IV had fired at Oliver. Get the panzer, he said.

The infantry watched as Oliver dismounted with his crew to look the situation over from behind a boulder using binoculars so that each man knew where the Mark IV lurked, and they put their heads together to come up with a plan. The crewmen climbed back through their hatches and settled into their seats. Oliver asked if everyone was ready.

“At Oliver’s command,” recalled Redle, “[Roy] Anderson thrust down on the throttle, and the Sherman suddenly roared around the granite shoulder; he yanked the sticks to align the tank on that Mark IV and heaved back on the sticks to lurch to a stop. [Bert] Bulen, with his head pressed into the sight rest, saw the ground as the 30-ton hulk rocked forward, and as it reared back and the sight came level, he swung the turret and squeezed off the first shot. His hand-eye coordination allowed him to place that first shot as the sights still moved across the target. [Ed] Sadowski slammed shell after shell into the recoiling breech as fast as Bulen fired, Bulen spinning the elevation/deflection wheels quickly and firing again and again. The German was out-maneuvered and was knocked out immediately.”[viii]

The 34th Infantry Division never did take Cassino. Three more bloody Allied assaults would fail to capture the town, which was to fall only when the Allies unhinged the Gustav Line in May. The American tankers kept their hand in for the next round, and in March, the 760th Tank Battalion and several tank destroyer battalions supported the 4th Indian and 2d New Zealand divisions in their unsuccessful attempt to capture Cassino.[ix]

See my website: World War II History by Harry Yeide

See the book from which this article largely derives: The Infantry's Armor

[i] FM 17-10, Armored Force Field Manual: Tactics and Technique, 7 March 1942.

[ii] FM 17-10, 142-143.

[iii] Tank Gunnery, The General Board, United States Forces, European Theater, not dated, 18. (Tank Gunnery)

[iv] History, 751st Tank Battalion. After-action report, 9th Infantry Division.

[v] Fazendin, 10, 76, 81.

[vi] Roger Fazendin, The 756th Tank Battalion in the Battle of Cassino, 1944 (Lincoln, Nebraska: iUniverse, Inc., 1991), 89-101, 114-117, 124. David Redle, letter to author, January 2008. “History” (actually the journal), 133d Infantry Regiment. AAR, 760th Tank Battalion.

[vii] “Action by 756 Tank Bn (US) in support of 133 Infantry Regiment (US) During the Crossing of the Rapido River and Subsequent Fighting in the Northeast End of Cassino,” Lieutenant Colonel Grenfell, Director of Military Training (Brit) Observer Staff, not dated.

[viii] Fazendin, 126-127.

[ix] AAR, Combat Command B, 1st Armored Division.