After a brief absence, I welcome the return of Harry Yeide to the Hatch. I hand the keyboard over to him to describe the lesser-known battle at Puffendorf. Over to you, Harry - Chieftain

At Operation Think Tank 2012, I mentioned the battle at Puffendorf as one of the few fights that included a large number of American and German tanks, and that you didn’t hear much abut it because the Yanks got their butts kicked. Here’s what happened...

Operation Queen

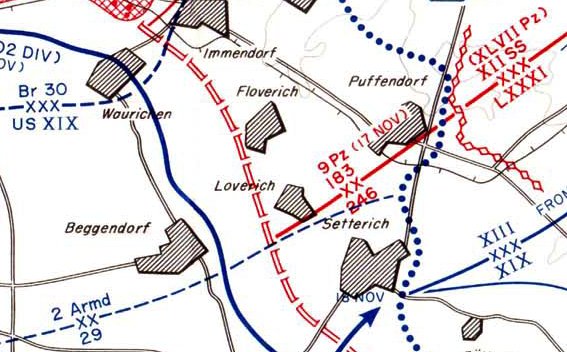

General Dwight Eisenhower opted to keep the pressure on the Germans during the winter of 1944 and ordered the 21st, 12th, and 6th Army groups to mount a broad-front offensive in November.[1] D-day for the 12th Army Group’s operation aimed at leaping the Roer River to the Rhine was November 11, weather permitting scheduled air support, and no later than November 16 under any circumstances. First Army, supported by Ninth Army, would make the main effort. Ninth Army, in turn, would get help from the British 30 Corps, which would operate in the northern end of the American zone against the West Wall defenses at Geilenkirchen and take over protection of the Americans’ long left flank. The American 84th Infantry Division (less one regimental combat team) was attached to the British for the operation to attack Geilenkirchen from the south.[2]

Lieutenant General Omar Bradley -- reflecting Eisenhower’s repeated guidance -- established the main goal of his operation as destruction of the German army west of the Rhine River.[3] First Army’s objective was to reach the Rhine, then to bridge it if possible. Ninth Army’s objective was to advance to the Rhine in the direction of Essen so it could bring the Ruhr under heavy artillery fire. It would then wheel northward to clear the west bank in cooperation with the British.[4]

Ninth Army at the beginning of November held a fourteen-mile front at the eastern end of the Dutch panhandle facing the Cologne plain. The left flank tied into the British Second Army. The right end linked with First Army’s VII Corps one mile south of Würselen. The XIX Corps line for much of its length ran parallel to the Siegfried Line and the Roer River, and only at Geilenkirchen did the westernmost West Wall defenses still hold firm.[5]

On November 8, Major General Alvan Gillem Jr.’s XIII Corps became operational and took responsibility for the north end of the Ninth Army line. The corps consisted of two nearly untested outfits, the 102d and 84th Infantry divisions (each less one regimental combat team), and the 7th Armored Division, recently released by the British.[6]

Major General Ray McLain’s XIX Corps, with the veteran 29th and 30th Infantry and 2d Armored divisions, was Ninth Army’s main punch. The 30th Infantry Division -- initially strengthened by the 335th RCT from the 84th Infantry Division -- had the immediate job of protecting VII Corps’ northern flank. Hobbs ordered the division to pivot on its point of contact with VII Corps at Würselen; the division would swing like a giant door south and east to crush any resistance against the 104th Infantry Division.[7] The other two divisions, meanwhile, would drive eastward.

Ninth Army’s AAR described the terrain in its zone as “flat, open ground stretching forward to the Roer River. Numerous small towns and villages, as well as built-up areas, dotted the land. These were used by the Germans for strong defensive positions; many of the towns were mutually supporting in their defenses. Mining and agriculture shaped the nature of this river valley; huge slag piles, factories, and miners’ houses were surrounded by beet and cabbage fields. The road net was good between the larger towns, but the minor roads were poor. Rainy weather reduced trafficability and roads were soon covered with mud. Traction was difficult off the roads.”[8]

Buildings that offered good fields of fire had been reinforced. Some had been turned into firing points for tanks. Cellars were often as stoutly built as bunkers. Fire trenches, foxholes, communications trenches, and ditches surrounded the villages. Fields, roads, and direct avenues of approach were liberally sown with mines. The slag piles -- which were up to 150 feet high -- were fortified and used as observation posts. And aerial photographs revealed that three belts of fortifications—at two, four, and eight kilometers from the Roer—protected Linnich. Two such bands shielded Jülich.[9]

* * *

The Germans would call this period the Third Battle of Aachen.

The Fifth Panzer Army commanding general, General der Panzertruppen Hasso-Eccard von Manteuffel, characterized his layered defenses in front of First and Ninth armies as a “‘spiderweb’ that caught the advancing or penetrating enemy.” Troops always had a fallback line ready. Defensive strongpoints were carefully selected to maximize fields of fire for antitank guns. The antitank guns, moreover, were often colocated with artillery and antiaircraft guns in minefield-ringed “artillery protective positions” to provide mutual support. Adapting tactics used successfully on the Somme and in Flanders a generation earlier, von Manteuffel withdrew three-quarters of his combat troops from the frontline to a “super-MLR” a thousand meters to the rear; this would protect them from preparatory artillery fire before any big attack. The scheme also meant that local commanders had to quickly launch counterattacks once Allied soldiers began to advance.[10]

Fifth Panzer Army expected to face a November offensive, and the stakes were immensely high. The Germans had to hold the Americans west of the Roer River, or the Führer’s planned massive counterstroke in the Ardennes would be preempted as the battle overran concentration areas. Indeed, the high command had factored the probability of a November attack by the Allies into its planning for the Ardennes operation. They just had not anticipated an attack on the scale of the one they got.[11]

General der Infanterie Friedrich Köchling’s LXXXI Corps would bear the brunt of the offensive. Köchling expected the main weight of the American attack to strike at Würselen. Secondary attacks were anticipated south of Geilenkirchen and in the Stolberg-Schevenhütte area. Köchling still had the 12th and 246th Volksgrenadier and 3d Panzergrenadier divisions under command. Köchling’s reserve consisted mainly of a reinforced battalion from each of the 12th and 246th Volksgrenadier divisions, two Tiger battalions (one securely bivouacked in underground garages between Immendorf and Setterich), an assault gun brigade, and a separate assault gun company.[12] The first half of November had provided the men with much-needed rest, and casualties had been low—on average only fifteen men killed or wounded per day in each division.[13]

Fifth Panzer Army had only the 9th Panzer and 15th Panzergrenadier divisions, which constituted XLVII Panzer Corps, available in reserve. The corps was deployed in the München-Gladbach area, from where it could support both XII SS and LXXXI corps. Commanders were aware that additional heavy units were marshaling east of the sector in preparation for the Ardennes offensive, including the 116th Panzer and the 2d and 12th SS Panzer divisions.[14]

* * *

Bad flying weather delayed the offensive from November 11 to 15. Each day, a code word was passed down the chain of command that indicated a twenty-four-hour delay.[15] Hodges was depressed by the weather, but the IX TAC commanding general, Major General Elwood

(Pete) Quesada, told him, “Don’t worry about that, General. Our planes will be there when you jump off, even if we have to crash-land every damned one of them on the way back.”[16]

November 16 dawned overcast and cloudy, but as the morning wore on, the skies cleared. “Man, look at that ball of fire,” Hodges told

Bradley. “But don’t look too hard; you’ll wear it out—or worse yet, maybe chase it away!”[17] At 1105 hours, according to the 104th Infantry Division’s unofficial history, men on the ground heard a continuous building roar, “like Niagara Falls.”[18] The throaty noise came from thousands of bomber engines. Air strikes commenced at 1145 hours.

Allied air forces conducted a preliminary bombardment, Operation Queen, that represented the largest close-support effort of the war. Different types of air strikes were used in the First and Ninth army zones—carpet-bombing of areas and “patch” bombing of specific targets, respectively. The goal in both cases was to destroy prepared positions, kill enemy personnel, and disrupt communications and supply.

General der Infanterie Friedrich Köchling felt the ground shaking at his headquarters in Niederzier, just east of the Roer. A flood of thoughts ran through his mind. But all of the orders had already been issued, the attack had long been expected. It was up to the men in the trenches.[19]

Hell on Wheels Attacks!

The XIX Corps was ready to roll at 1245 hours, per orders. From north to south, the 2d Armored and 29th and 30th Infantry divisions jumped off without the usual artillery preparation in a bid to achieve tactical surprise. Farther north, XIII Corps’ 102d Infantry Division also pushed off near Immendorf to cover the 2d Armored Division’s left flank.[20]

Fighter-bombers from the XXIX TAC had been isolating and softening up the battlefield since the beginning of November. Aircraft struck fortified villages with incendiary, napalm, and high-explosive bombs whenever reconnaissance indicated activity in them. Marshaling yards, supply depots, and rail chokepoints received continual attention.[21]

As in much of the VII Corps sector, initial resistance was relatively light—at least everywhere except Würselen.[22] But in some cases, “initial” lasted only minutes.

As in much of the VII Corps sector, initial resistance was relatively light—at least everywhere except Würselen.[22] But in some cases, “initial” lasted only minutes.

Major General Ernest Harmon, commanding the 2d Armored Division, was extremely concerned that the downpours that had delayed D-day would create mud so deep that his tanks would bog down. Harmon personally mounted a Sherman in the division’s concentration area west of the Würm and drove around the fields. The tank could manage only two to three miles per hour in low gear. Still worried, he turned to the tank commander and asked, “Can we make it, sergeant?”

“Yes, sir.”

Harmon was satisfied. If the sergeant and his Sherman could make it, the division could, too. Harmon told Simpson that the mud would not pose an insurmountable problem.[23]

* * *

The 2d Armored Division, reinforced by the 102d Infantry Division’s 406th RCT; the 2d Battalion, 119th Infantry Regiment; and Squadron B, 2d Fife and Forfar Yeomanry, attacked toward Puffendorf and Gereonsweiler. Because of Hell on Wheels’ narrow front, only CCB participated in the first thrust. The division’s mission was to sever the Germans’ last north-south communications lines west of the Roer, then reassemble to cross the river through a bridgehead to be established by the 29th Infantry Division.

The 183d and 246th Volksgrenadier divisions could offer little resistance as Brigadier General Isaac White’s CCB overran four towns during the afternoon. By day’s end, the combat command had easily taken its initial objectives, including high ground next to Puffendorf. The 246th Volksgrenadiers reported to Köchling, “The hole can no longer be mended.”

Only at Apweiler, where German guns in two minutes knocked out seven Shermans crawling slowly through mud, did the division suffer a significant setback.[24] Generalleutnant Wolfgang Lange had taken the risk of rushing his reserve—his fusilier battalion and Hetzer-equipped Panzerjäger company—to Apweiler in broad daylight. It was these assault guns that claimed the CCB Shermans after their crews had watched patiently until the Americans were within three hundred yards before opening fire.[25]

Combat Command A waited for the 29th Infantry Division to clear the town of Setterich and capture a crossing there over a major antitank ditch before it entered the fight. Harmon’s impatience with the slow speed of this operation would build over the next few days. Queries to Major General Charles Gerhardt, commanding the 29th Infantry Division, on the subject from the corps commander and his deputy suggest that Harmon asked them to intervene, too. Gerhardt, an old cavalryman who relentlessly rode his National Guard division, invariably then applied heat of his own to his regimental commanders.[26]

* * *

About dusk on November 16, von Manteuffel ordered a general withdrawal to the second defense line and placed a Kampfgruppe from the 116th Panzer Division at the disposal of LXXXI Corps. That night, Fifth Panzer Army shifted its reserve 15th Panzergrenadier Division into the area south of Erkelenz and the 9th Panzer Division west of Linnich so they would be available in a timely fashion west of the Roer River. Von Manteuffel detached Major Lange’s 506th Schwere Panzer Abteilung (with thirty-six battle-ready Royal Tigers)from LXXXI Corps and attached them to the 9th Panzer Division.[27] Perhaps, in light of the alarming reports from Puffendorf of a 2d Armored Division breakthrough, von Manteuffel already had something in mind.

* * *

By that sa me evening, the 29th Division commanding general, Gerhardt, had concluded that his boys were not going to get the job in Setterich done by themselves. (Indeed, his opposite number at about the same time reported that morale among his tired troops was excellent because of their success thus far in beating off attacks by a better-equipped and more numerous foe.)[28] Gerhardt phoned Harmon at the Hell on Wheels CP and invited the armored division to lend a hand. Gerhardt also asked if his infantry could work in the 2d Armored’s zone, to which Harmon readily agreed. Next, Gerhardt contacted the commander of the 116th Infantry Regiment and told him to use whatever troops necessary to capture Setterich. Another call to Hell on Wheels produced an offer of seventy-five tanks. “Now we’re talking business,” said Gerhardt.[29]

me evening, the 29th Division commanding general, Gerhardt, had concluded that his boys were not going to get the job in Setterich done by themselves. (Indeed, his opposite number at about the same time reported that morale among his tired troops was excellent because of their success thus far in beating off attacks by a better-equipped and more numerous foe.)[28] Gerhardt phoned Harmon at the Hell on Wheels CP and invited the armored division to lend a hand. Gerhardt also asked if his infantry could work in the 2d Armored’s zone, to which Harmon readily agreed. Next, Gerhardt contacted the commander of the 116th Infantry Regiment and told him to use whatever troops necessary to capture Setterich. Another call to Hell on Wheels produced an offer of seventy-five tanks. “Now we’re talking business,” said Gerhardt.[29]

And so, reinforced by the 2d Battalion, the 1st Battalion, 116th Infantry, entered Setterich the next day, supported by tanks from both the 747th Tank Battalion and 2d Armored Division. This time, the Shermans rolled up to the trenches and blasted any resistance. Soon, the doughs were moving from house to house, rooting out defenders. Another day of stiff fighting was necessary to finish the job.[30]

The Panzers Strike Back

While the 29th Infantry Division inched forward against fierce resistance on 17 November, the 2d Armored Division battled both mud and a full-blown German counterattack at Puffendorf. The Germans viewed the penetration by Hell on Wheels as the most pressing threat in the sector. Generalfeldmarschal Gerd von Rundstedt authorized the use of the reserve 9th Panzer and 15th Panzergrenadier divisions to contain the menace. German radio, anticipating victory, called the counterattack the “largest and most decisive tank action on the Western Front.” Jack Bell, a war correspondent for the Chicago Daily News Service, called it “a battle virtually lost in the shuffle of world-shaking events. It was a battle which shook the earth of this sector.”[31]

The Panthers from the 9th Panzer Division—commanded by Generalmajor Harald Freiherr von Elverfeldt—accompanied by the 506th Schwere Panzer Abteilung’s Royal Tigers, struck early in the morning.[32] The Mark VI Royal Tiger was a 70-ton monster with 150mm (6 inches) of sloped front armor and an 88mm gun that had an even higher muzzle velocity than that found on the feared Tiger I.[33]

The Panthers from the 9th Panzer Division—commanded by Generalmajor Harald Freiherr von Elverfeldt—accompanied by the 506th Schwere Panzer Abteilung’s Royal Tigers, struck early in the morning.[32] The Mark VI Royal Tiger was a 70-ton monster with 150mm (6 inches) of sloped front armor and an 88mm gun that had an even higher muzzle velocity than that found on the feared Tiger I.[33]

Colonel Paul Disney’s Task Force 1 (CCB) was just forming up for the day’s attack when twenty to thirty panzers, supported by infantry and artillery, burst through heavy morning mist into its positions. Artillery and small-arms fire had already been striking the assembly area since the early hours. Shortly after dawn, high-velocity armor-piercing (AP) shells began to plow furrows in the earth among the tanks of 1st Battalion, 67th Armored Regiment, just as the 2d Battalion was arriving for the attack. Some of the fire was long-range gunnery by Royal Tigers, several of which Fifth Panzer Army commanding general von Manteuffel had ordered dug in on high ground because they were suffering high numbers of breakdowns.[34]

A tank battle ensued, which the Germans won decisively. The American tanks were drawn up on line and lacked the depth to support their own advance by fire. The high-velocity German guns knocked out Shermans from ranges starting at three thousand yards. Shells from 75mm and 76mm Sherman guns mostly bounced harmlessly off the panzers’ front armor. Only a shot from the side or rear—or a lucky hit on a track or on the underside of the Panther’s gun mantlet (the round would ricochet through the thin roof armor)—could stop the German tanks. The panzers also had wider tracks than the Shermans and were better able to maneuver in the deep mud.

One report captured the essence of the action: “Sergeant Julian Czekanski, a Company D . . . tank commander, sighted a German tank and fired on it without apparent effect. The tanks on the right flank were now taking direct hits. One of them, Lieutenant Karl’s, flared up like burning celluloid, but all five crew members escaped. There were too many tanks in the draw, too little room for maneuver. Two enemy Mark VI and four Mark V tanks were observed scuttling from the woods on the western fringe of Gereonsweiler through the mist that clung persistently to the high ground. A fall of bluish smoke sifted down into the draw. Two more mediums on the right went up in flames. Then in the space of a few minutes, four of the light tanks were burning.”[35]

With some companies reduced to less than platoons, and with ammunition running out, the 1st and 2d battalions at 1600 hours disengaged and withdrew to the outskirts of Puffendorf. During the withdrawal, Sergeant Czekanski’s tank suffered a direct hit that wounded him and set the vehicle on fire. The task force hunkered down to defend the town against recapture.

Czekanski’s platoon leader, Lieutenant Pendleton, sat in a lane on the edge of town. His tank had one round of AP, two of smoke, and six of HE remaining. Pendleton spotted a Panther moving across his front but concluded that he was in no position to seek out battle. The Mark V crew had spotted him, though, and the Panther fired as it advanced. Pendleton’s gunner fired two rounds of smoke, and the panzer retreated. Soon, it approached again. Pendleton fired four rounds of HE, one of which struck the driver’s hatch and convinced the panzer crew to draw off again.

The company commander, Lieutenant Robert E. Lee, arrived just as Pendleton was dismounting from his tank. “For God’s sake, Lee, get me some help!” Pendleton shouted.

The company commander, Lieutenant Robert E. Lee, arrived just as Pendleton was dismounting from his tank. “For God’s sake, Lee, get me some help!” Pendleton shouted.

“What do you think that little gadget behind me is?”

Lee was guiding into position Lieutenant Cecil Hunnicutt’s platoon from the 702d Tank Destroyer Battalion. Just then, the Panther reappeared and fired an AP round down the lane, barely missing the first M36.

“That was direct fire, wasn’t it?” asked Hunnicutt.

“You’re goddamned right it was!” replied Pendleton.

Hunnicutt pulled his tank destroyer into position and fired two rounds after the Panther, which ended the dispute for the moment. Artillery fire also discouraged the Germans; three Royal Tigers were set ablaze in a single barrage.

Soon, T2 tank recovery vehicles and half-tracks carrying ammo for the tank guns began to arrive. Nevertheless, had the Germans pressed the attack during the night, supplies probably would not have been adequate to defend Puffendorf.[36]

* * *

Ninth Panzer Division attacks struck other CCB task forces during the morning. The M36s (and a few remaining M10s) from the attached 702d Tank Destroyer Battalion engaged the attackers and knocked out six panzers during the day. The newly deployed M36, which carried a 90mm gun, was undergoing its first large-scale battle test. The 90mm could kill the Panther and Tiger at ordinary combat ranges, but the Royal Tiger demanded the simultaneous attention of two or more M36s, and generally a side shot even then. That said, one M36 crew knocked out a Royal Tiger north of Friealdenhoven on November 19 at twelve hundred yards; the 90mm round holed the turret side, passed entirely through the breach ring of the 88mm gun, and nearly penetrated the far turret wall.

* * *

The day’s fighting cost the 2d Armored Division eighteen medium and seven light tanks destroyed and about the same number damaged and out of action. Fifty-six men were killed and 281 wounded, and 26 went missing in action (which for tankers often meant burned to unrecognizable cinders in their Shermans). The Americans claimed seventeen panzers destroyed.[37]

See my website: World War II History by Harry Yeide

See the book from which this article derives: The Longest Battle

[1] Charles B. MacDonald, The Siegfried Line Campaign: United States Army in World War II, The European Theater of Operations (Washington, DC: Office of the Chief of Military History, Department of the Army, 1993), 390-392. Hereafter MacDonald, The Siegfried Line Campaign.

[2] AAR, Ninth Army.

[3] Omar N. Bradley, A Soldier’s Story (New York, NY: The Modern Library, 1999), 439. Hereafter Bradley.

[4] Ninth United States Army, Operations, IV, Offensive in November, February 1945, 1–3.

[5] AAR, Ninth Army.

[6] Ibid.

[7] Ninth United States Army, Operations, IV, Offensive in November, February 1945, 11.

[8] AAR, Ninth Army.

[9] Ninth United States Army, Operations, IV, Offensive in November, February 1945, 2.

[10] General der Panzertruppen Hasso-Eccard Von Manteuffel, commanding general, Fifth Panzer Army, “Statement by General von Manteuffel,” MS # A-857, not dated, National Archives. Hereafter Von Manteuffel. General der Infanterie Friedrich Köchling, Commanding General, LXXXI Corps, “The Battle of the Aachen Sector,” MS # A-989 to MS # A-998, series begins 16 December 1945, National Archives. Hereafter Köchling.

[11] Generalmajor Carl Wagener, Chief of Staff, Fifth Panzer Army, “The Action of the Fifth Panzer Army During the American November Offensive,” MS # A-863, 12 December 1945, National Archives.

[12] Köchling. Tagesmeldungen, LXXXI Armee Korps. Ia, Zustandsberichte, 10.10.–17.12.1944, LXXXI Armee Korps.

[13] Tagesmeldungen, LXXXI Armee Korps.

[14] Conquer, The Story of the Ninth Army (Washington, DC: Infantry Journal Press, 1947), 84. Hereafter Conquer. MacDonald, The Siegfried Line Campaign, Map VII. Hereafter MacDonald, The Siegfried Line Campaign. Kriegstagebuch, Kampfverlauf, 22.10–31.12.44, LXXXI Armee Korps. General der Panzertruppen Heinrich Von Lüttwitz, “The 47. Pz Corps in the Rhineland from 23 Oct-5 Dec 1944,” MS # B-367, 11 January 1947, National Archives, 1.

[15] G-3 Report of Operations, 1st Infantry Division.

[16] Bradley, 440.

[17] Ibid.

[18] Leo A., Hoegh and Howard J. Doyle, Timberwolf Tracks, The History of the 104th Infantry Division, 1942-1945 (Washington, DC: Infantry Journal Press, 1946), 115.

[19] Kriegstagebuch, Kampfverlauf, 22.10–31.12.44, LXXXI Armee Korps. Köchling.

[20] Conquer, 89.

[21] Ibid, 79–80.

[22] Ibid, 89.

[23] Ibid, 86.

[24] Ninth United States Army, Operations, IV, Offensive in November, February 1945, 36–37, 48ff.

[25] Generalleutnant Wolfgang Lange, “183d Volksgrenadier Division (Sep 1944-25 Jan 1945),” MS # B-753, not dated, National Archives, 10, 13. Hereafter Lange. Kriegstagebuch, Kampfverlauf, 22.10–31.12.44, LXXXI Armee Korps. Houston, 309.

[26] Ninth United States Army, Operations, IV, Offensive in November, February 1945, 36–37, 48ff. Journal, 29th Infantry Division. Joseph Balkoski, Beyond the Beachhead, The 29th Infantry Division in Normandy (Mechanicsburg, Pennsylvania: Stackpole Books, 1999), 44ff.

[27] Kriegstagebuch, Kampfverlauf, 22.10–31.12.44, LXXXI Armee Korps. Tagesmeldungen, LXXXI Armee Korps. Wagener.

[28] Tagesmeldungen, LXXXI Armee Korps.

[29] Journal, 29th Infantry Division.

[30] Ninth United States Army, Operations, IV, Offensive in November, February 1945, 82ff.

[31] MacDonald, The Siegfried Line Campaign, 530. Jack Bell, ”Second Armored Drove Back Massed Tigers, Panthers in Roer River Battle,” Chicago Daily News Service, 24, included in Second Armored Division, 2d Armored Division, 1945. Hereafter Bell.

[32] MacDonald, The Siegfried Line Campaign, 530.

[33] Dr. F. M. Von Senger und Etterlin, German Tanks of World War II (New York, NY: Galahad Books, 1969), 200–201.

[34] Von Manteuffel. AAR, 2d Armored Division.

[35] Ninth United States Army, Operations, IV, Offensive in November, February 1945, 68.

[36] Ibid, 69. Wolfgang Schneider, Tigers in Combat I, errata posted at J.J. Fedorowicz Publishing, Inc’s web site, www.jjfpub.mb.ca/tigers_in_combat_i.htm, entry for 17 November 1944.

[37] Houston, 310–313. MacDonald, The Siegfried Line Campaign, 531. Bell, 24ff. Ninth United States Army, Operations, IV, Offensive in November, February 1945, 67ff.