History Spotlight: Operation Mincemeat

Off the coast of Huelva Spain, a waterlogged and decomposing body was found by a local fisherman on April 30, 1943. The deceased gentleman appeared to be a British officer of at least some importance. He was dressed in uniform and carried a black briefcase chained to his waist. He wore a life preserver, but it appeared to have done him little good. Hypothermia was thought to be a likely cause of death upon initial discovery.

The body was brought to the local Spanish authorities. According to the man’s identification he was Major William Martin with the British Royal Marines. The authorities immediately called the nearest British consular representative, Francis Haselden. Wanting to avoid any sort of breach of protocol, Haselden would not take custody of the items that were found with the body. The Spanish authorities, technically a neutral entity, tipped off local German intelligence operatives and offered them a chance to examine the materials found.

A rather official looking military envelope was contained in the briefcase. The Germans were able to extract the contents without breaking the seal by inserting a rod into the envelope and spinning the documents into a tight enough cylinder to be pulled from a small opening. They were shocked by their good fortune. They’d just stumbled across a personal letter from Lt. Gen. Sir Archibald Nye, Vice Chief of the Imperial General Staff. After sifting through the information, it was discovered that the Allied plan, Operation Husky, intended to land troops from Egypt and Libya in Greece and Sardinia, two areas currently occupied by German Forces.

After taking the time to determine the credibility of the information, a decision was made by top German officials to redirect their forces to Greece, Sardinia, and Corsica. They’d been expecting an attack from the Allied forces that were then securing North Africa, sometime in the near future. The German movement thinned the defenses along other Mediterranean footholds, including Sicily.

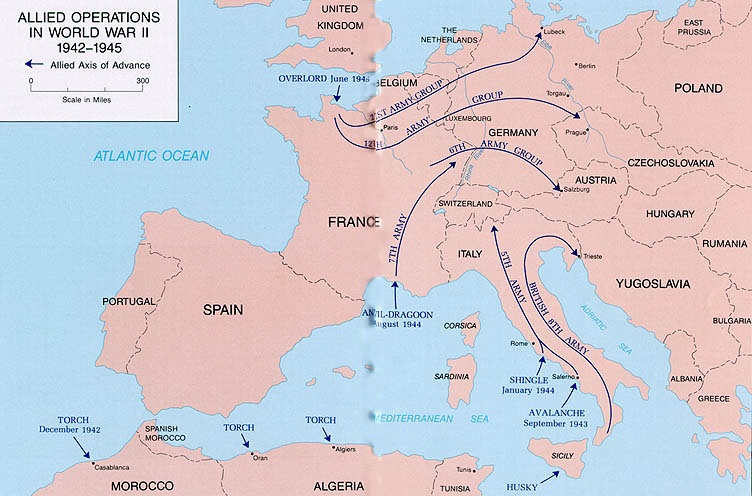

On July 9, 1943, just a few months after the body of a British officer turned up on the coast of Spain, seemingly to have avoided death during a plane crash only to perish in the sea, the Allied forces launched their attack from North Africa. Not to Greece, the Balkans, or Corsica, but to Sicily.

By gaining control of Sicily the Allies hoped to open many Mediterranean sea-lanes and give themselves a jumping off point for a full invasion of Italy.

“Everyone but a bloody fool would know that it’s Sicily,” Winston Churchill is reported to have said in regard to their initial plans for Operation Husky.

The German Military had just been duped by an elaborate and daring scheme of misinformation. There were insufficient forces to repel the attack, and by August the Allies had secured the island. From there, they were able to continue onto the Italian mainland and oust Mussolini from power; delivering a mortal blow to the hopes of the Axis.

Operation Mincemeat was grown from an idea initially drafted, albeit in a much different form, by none other than Ian Fleming, the author responsible for the creation of James Bond. In 1939, working in Naval Intelligence, he composed a memo that outlined several ideas for spreading misinformation to the enemy. He likely obtained the idea from Basil Thomson, author of 1930s detective novels.

When the time came to begin Operation Barclay, a plan to engage in widespread deception to throw off the German understanding of Operation Husky, Flight Lt. Charles Cholmondley and Lt. Cmdr. Ewen Montagu worked together to flesh out the details for Operation Mincemeat.

They needed a body. After much difficulty in finding a match for their ‘drowned/hypothermia suffering’ officer, a 34-year-old Welsh man named Glyndwr Michael was unfortunate enough to die. He’d apparently committed suicide by eating rat poison, but the pathologist assured them that there was very little evidence in the body to contradict the notion that they were attempting to insert into the German inspectors—that is, they’d have every reason to believe the man suffered hypothermic shock and drowned.

The identity of Major William Martin was a complete fabrication. Montagu and Cholmandeley went the whole nine yards; not only did they have false documents created to put on file for the British Military Records, they also included love letters and photos from Martin’s ‘fiance’ Pam, as well as a diamond engagement ring in the briefcase. Additionally, they put receipts and other bills and notes on his person so as to allow for the construction of a time-line by the Germans when the body was discovered. There was also a letter from his father and overdraft statements from his bank. They even went so far as to include used bus and theater tickets; everything a real person might happen to have on them on any ordinary day.

The utmost care was taken when they drafted the documents that contained the sensitive information about Operation Husky. There could be no doubt as to the veracity of the letters.

In order to transport the body from England to the coast of Spain, Charles Fraser-Smith, thought to be the inspiration for the character Q in the James bond books, designed a steel canister filled with dry ice. As the ice dissipated it displaced all the oxygen in the container with carbon dioxide thereby preserving the body.

After the body was pushed into the sea the gamble began. Would it make it to shore? Would it be discovered with the documents? Would it be turned over to the Germans? Would the Germans see through the falsehoods?

After the authorities contacted the British representative, Francis Haselden, who did not take custody of the Martin’s belongings (he was in on the plan), the British Intelligence offices staged several frantic calls looking for the briefcase.

There is reason to believe that the Germans did not believe in their ‘good fortune’. There were several aspects of the situation that should have aroused suspicion. Including the autopsy of the body performed in Spain; it was clear that the man had not been at sea for as long as the dates on the items he was carrying indicated. Not enough of him was missing, the crabs and fish hadn’t been at him enough, his hair wasn’t brittle enough, he didn’t have water in his lungs, and there were no bruises on his body from the ‘crash’.

Perhaps the Germans realized that no matter what the information actually indicated, their forces needed to be bulked up in those other locations. Hitler did fear and suspect an attack in those regions. Perhaps the Germans simply confused themselves; thinking that they knew that the Allies were misleading them, and tried to counter that counter-intelligence.

Trying to figure out who knew what, and who knew that they knew what, and who knew that they knew that they knew what, and what they knew, is probably what we’ll never know.

In the end, the allies were successful in invading Sicily. In that sense, Operation Mincemeat, as a part of Operation Barclay, as a supporting action to Operation Husky, is counted as a major success.